The Earth's surface isn't one solid rock; it's composed of several massive chunks called tectonic plates. These plates gradually rotate, sometimes crashing into, separating from, or sliding under one another. Scientists have recently made a startling discovery.

Under the Pacific Ocean near Canada's Vancouver Island, a tectonic plate is splitting into two. This area, known as the Cascadia Subduction Zone, is approaching its demise. Will this lead to a massive earthquake or catastrophe? This research is published in the

Earth's upper layer, the crust, consists of multiple plates floating on semi-melted rocks. These plates are interconnected but slowly move, sometimes rubbing against or pulling away from each other. The most dangerous process is subduction—where one plate slips beneath another, sparking volcanic eruptions and earthquakes.

Source: aajtak

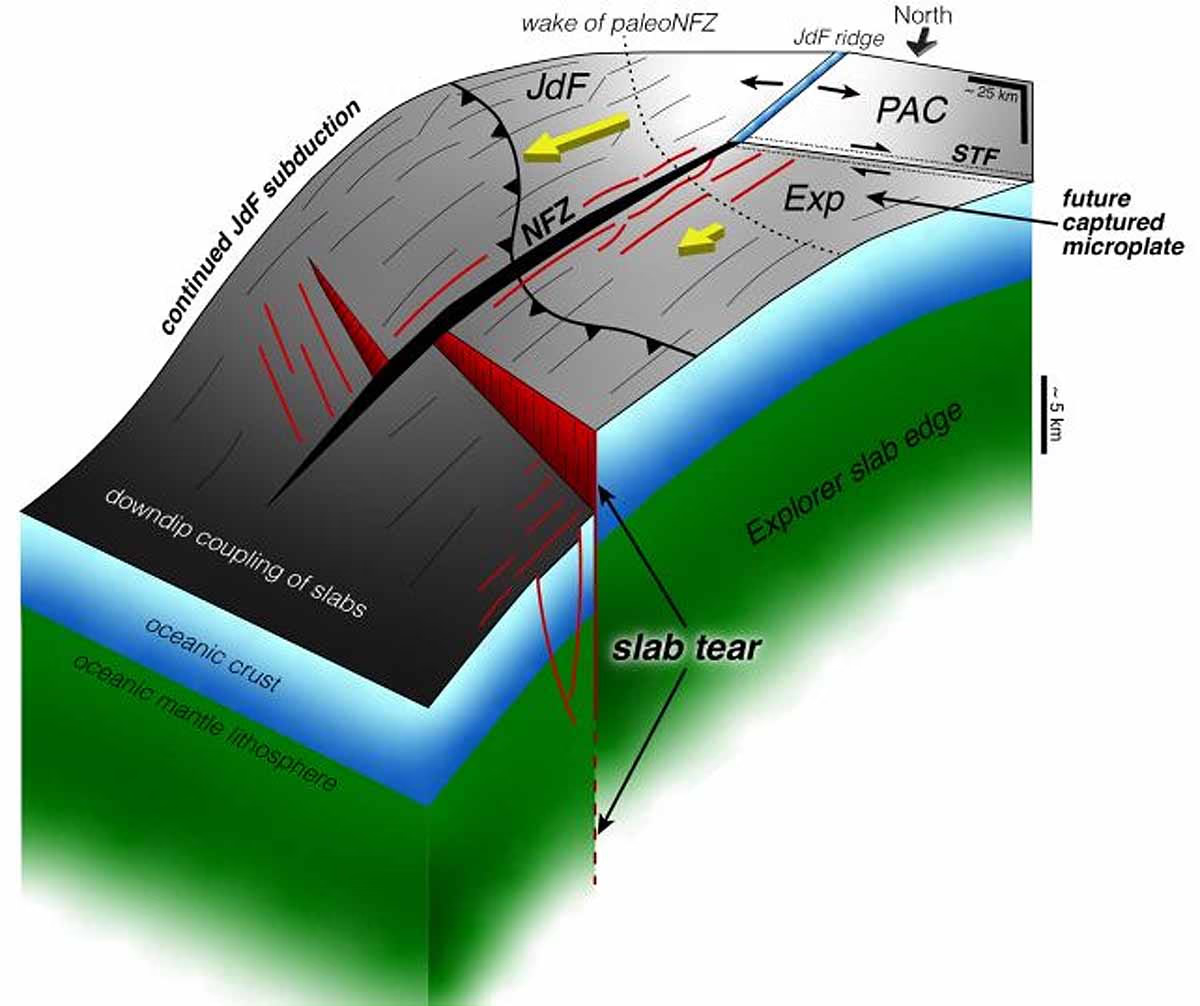

The Cascadia Subduction Zone is located in the northern Pacific. It's where four plates converge: the Explorer, Juan de Fuca, Pacific, and North American. The Explorer and Juan de Fuca plates are sliding under the North American plate, creating a complex scenario.

Brandon Shuck from Louisiana State University compares initiating a subduction zone to pushing a train uphill—it's laborious. But once it starts, it races downhill, difficult to stop, requiring a catastrophe like derailment to halt.

Shuck and his colleagues conducted seismic imaging from a ship, akin to sending sound waves from the sea floor like an ultrasound. They also utilized earthquake waves bouncing within the Earth, revealing the Explorer Plate breaking apart at Cascadia's northern tip.

Several major faults and fractures were discovered, the largest being a 75-kilometer-long fault tearing the plate apart, taut like a rubber band about to snap.

Source: aajtak

Subduction zone splitting may seem normal. If plates continually shoved together, geological history would vanish. Nature prevents this by fracturing plates into smaller microplates, some becoming seismically inactive, cut from the main system.

As more sections fracture, subduction may cease, reducing plate weight and halting the downward pull. Shuck asserts this slow breakdown affirms volcanic rock ages, either aging or emerging newly.

No need for panic yet. This slow-motion process spans millions of years, but localized tremors may occur as fractures emerge. Cascadia is already a significant threat; in 1700, a magnitude 9 earthquake sent tsunamis to Japan. The zone's complete rupture could devastate Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia, though scientists view it as a death knell.

This study enhances comprehension of Earth's inner workings, potentially refining earthquake predictions. Scientists will gather more data. Shuck likens it to a train race—once in motion, stopping is arduous, yet it heralds a fresh start. Earth always transforms. The Pacific's undersea rupture reminds us our planet is vibrantly alive, warranting cautious vigilance.