Mexico faces a swift rise in flesh-eating screwworm cases, posing a severe threat to both animals and humans. By August 17, 2025, 5,086 cases in animals have been reported in Mexico, marking a 53% increase from July's figures.

Out of these, 649 cases remain active. This data, previously undisclosed, stems from Mexican government records. Experts express concern over the rise, particularly during the warm season, indicating control measures appear ineffective.

Primarily affecting cattle, the infestation has also been identified in dogs, horses, and sheep. Since its onset in 2023, this outbreak spread from Central America northward, nearing the U.S. border. Let's delve into the details of the screwworm: what it is, how it spreads, and its impact.

What is Screwworm? How Does the Infection Spread?

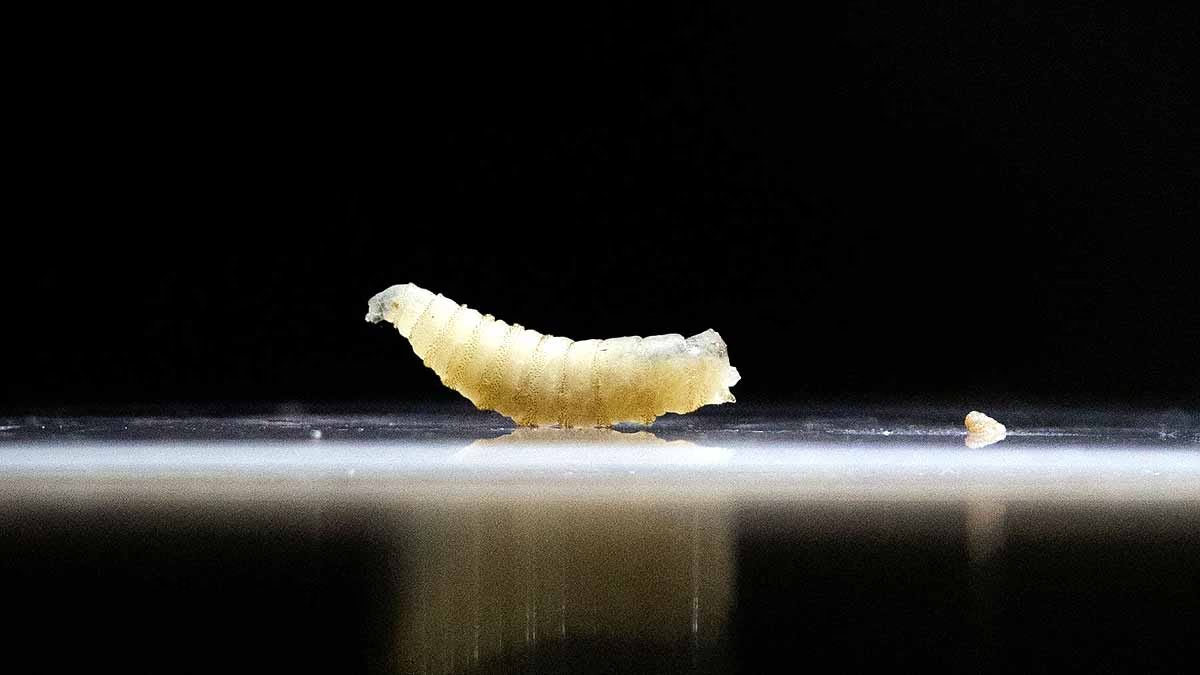

The screwworm is a parasitic entity, scientifically termed the New World Screwworm. It lays hundreds of eggs in the wounds of warm-blooded creatures like cows, sheep, dogs, horses, and humans. Once hatched, the larvae burrow into living flesh with their sharp, hook-like mouths.

Feeding on flesh, they enlarge the wound, and without treatment, can lead to the host's demise. The name 'screwworm' derives from their appearance as they burrow, resembling a screw.

Source: aajtak

How It Spreads:

Female flies lay eggs near wounds or orifices such as the nose, eyes, or mouth. The spread accelerates in warm weather. Beginning in Central America in 2023 (specifically Panama, Costa Rica, Honduras, Guatemala), the screwworm reached Mexico and is now advancing north.

Treatment entails wound cleaning, larva removal, and antibiotics. Delayed action can result in fatal infections.

According to the U.S Department of Agriculture (USDA), while common in South America, the screwworm was eradicated from the U.S and Mexico in the 1960s, only to resurface now.

Statistics and Reasons for the Surge

Mexican government statistics reveal that the cases were few in July, but surged 53% by August, totaling 5,086 cases, with 649 active. Most instances occur in Chiapas, southern Mexico, where 41 humans have fallen ill due to the parasite.

Heat: Expert Neil Wilkins, CEO of the East Foundation, remarks on the alarming 50% monthly rise, emphasizing reproductive spikes in warm climates, reflecting inadequate control measures.

Northward spread: Since 2023, the pest has migrated from Central America to Mexico. Initiatives by the Panama-US Commission (COPEG) using sterile flies have faltered against the backdrop of livestock trade and agricultural expansion.

Additional factors: Untreated animal wounds and increased travel contribute to the spread.

As reported by Al Jazeera, Mexico faced a loss of $1.3 billion last year, driven mainly by halted livestock exports.

Impact on Animals, Humans, and the Economy

The devastation wreaked by screwworms is profound, ravaging livestock and wildlife.

On Animals:

Predominantly affecting cattle, the larvae devour the flesh, weakening the creature and often resulting in death. Mexico's livestock industry has suffered, while potential spread in the U.S. could cost Texas, a leading livestock state, $1.8 billion.

On Humans:

Though rare, infection can be deadly. In Mexico, 41 cases have been documented, mostly in Chiapas. The first U.S. human case emerged on August 4, 2025, involving a traveler returning from El Salvador. After Maryland's health department and the CDC investigated, treatment proved effective, though it was a travel-linked case.

Economic Impact:

With livestock exports halted, USDA warns of $100 billion in threat-induced activities. Mexico is investing $51 million in a sterile fly facility to combat the issue.

Prevention Efforts: Sterile Flies and Global Collaboration

To counter screwworms, an old yet effective method is employed: the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT). By sterilizing male flies with radiation before releasing them to mate with wild females, egg fertilization is rendered ineffective.

Mexico and the U.S. are proactive: Mexico is constructing a $51 million facility in the south. Panama's COPEG plant generates 20 million pupae per week, with potential to increase up to 100 million during peak outbreaks. USDA is dispatching a team to Mexico bi-weekly to ensure protocol adherence.

U.S. Measures: A new sterile fly facility is in development in Texas, anticipated to complete within 2-3 years. Traps installed at the border, halted animal imports, and emergency drug approvals, such as ivermectin. Ongoing research focuses on gene editing and vaccinations.

Further Actions: Immediate treatment of animal wounds and stringent surveillance. USDA has fortified the biological barrier in Panama.

If spread halts, a demand for 500 million sterile flies weekly will remain. The 53% surge in screwworm cases in Mexico serves as an alert. This live-animal-eating parasite brushes against U.S. borders, threatening billion-dollar losses. Proliferation is expedited by heat and travel, but with sterile flies and international cooperation, control is achievable.