'Blood and water can't flow together,' said Prime Minister Narendra Modi back in 2016 in response to the Uri attack orchestrated by Pakistan, which claimed the lives of 18 Indian soldiers. He was alluding to the Indus Water Treaty. Despite the attack and continued terrorism, India had not suspended the agreement—until recently. Following the April 22 attack in Pahalgam, where terrorists targeted tourists leading to 26 deaths, India has, for the first time, suspended the Indus Water Treaty.

The Fate of Rivers Controlled by PAK?

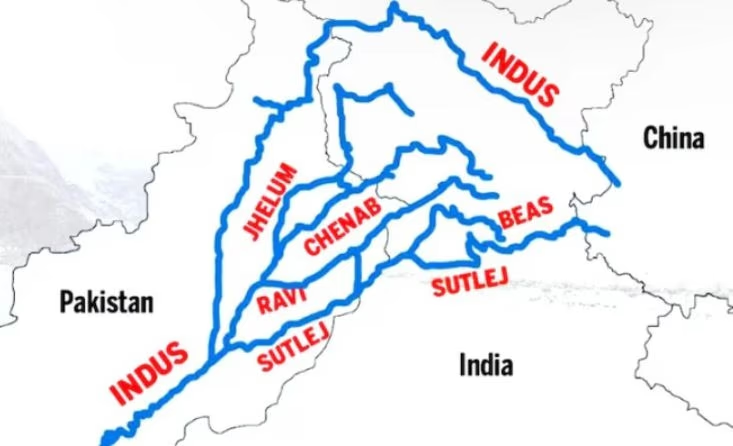

India decided to halt the treaty unless Pakistan takes firm action against cross-border terrorism. This significant move by New Delhi, seen as pivotal in India-Pakistan relations, prompts crucial questions. With the Indus Water Treaty now suspended, allowing India to control the western rivers (Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum), what becomes of these rivers' waters? Can India effectively harness and potentially reroute these resources for its use? How long could it take for India to stop the flow to Pakistan entirely with its infrastructure?

Read More:

Experts assert that while India has legal and diplomatic leeway to build infrastructure to hold and divert the western rivers' water, its immediate ability to do so is limited by current infrastructural constraints and the magnitude of projects yet undeveloped.

What the Treaty Means for Pakistan?

Pakistan utilizes roughly 93% of the Indus River System for irrigation and power generation, with approximately 80% of its agriculture relying on these waters. Shows how vital the Indus System is to Pakistan's very existence. According to Bilawal Bhutto, head of the Pakistan Peoples Party, 'Either our water will flow, or their blood will.'

Source: aajtak

Expert Brahma Chellaney wrote on X, 'For 65 years, India has been burdened by the Indus Water Treaty without benefits, even as it remains one of the world's most generous water-sharing agreements. Post-treaty, India has primarily used water from the eastern rivers—Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—for irrigation and hydropower in Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan, consuming about 95% of its allocated share due to major dams like Bhakra, Pong, and Ranjit Sagar on these rivers.

India's Minimal Use of Western Rivers

Using the western rivers more minimally, India's projects are confined to hydro projects like the Kishanganga (330 MW) and the under-construction Ratle (850 MW), which don't disrupt river flows into Pakistan. Despite the potential due to the terrain of the western rivers, India's existing storage is zero due to treaty restrictions.

The Himalayan rivers boast a hydropower potential exceeding 150,000 MW, thanks to steep slopes, perennial flow, and glacier origins.

Implications of Suspending the Treaty

India's suspension of the treaty could remove constraints, allowing exploration of new storage and diversion options. However, India lacks the hydropower infrastructure on the western rivers to immediately use or halt significant water flows to Pakistan.

Read More:

By suspending the Indus Water Treaty, India no longer needs to notify Pakistan of projects on western rivers, neither share data, nor facilitate official visits, effectively halting cooperation under the treaty. According to 'Indian Express,' as per P.K. Saxena, former Indian Commissioner for Indus Waters.

Pakistan's Consent Not Required

Saxena indicated in reports that India can proceed with reservoir flushing on Kishanganga, extending dam life by clearing sediment, typically every 5-10 years, using dredging or sluicing.

Not sharing flow information beforehand may leave Pakistan uninformed about potential drought or flood threats.

Source: aajtak

The PTI news agency reports that current dams and barrages on India's western rivers Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab, along with their tributaries, can store less than one MAF of water. Experts like Sushant Sareen say though technically, India may divert or store waters of the western rivers, practically, significant changes are unlikely without completed projects.

No Immediate Obstacles in Project Development

Sareen on X expressed, 'Not immediately, but the construction of dams underway can continue without Pakistani interference to ensure we can withhold waters when Pakistan needs them most. However, constructing further reservoirs and structures for diversion will take years.'

Read More:

Without adequate western river infrastructure, India can't immediately alter Pakistan-bound water flows. But had India prepared projects for these rivers? Yes, even before suspending the treaty, India planned and was working on several western river projects to increase water use, though these focus on hydro generation rather than large storage reservoirs.

Major Projects on Chenab and Ravi River

Key projects include hydroelectric works like Pakal Dul and Marusudar (1,000 MW) on Chenab’s tributaries, Ratle (850 MW), Kiru (624 MW), and Sawalkot (1,856 MW) on Chenab itself. Western river projects currently running store limited water, such as Kishanganga’s 18.35 MCM reservoir on Jhelum.

After completing the Ujh multipurpose project on the Ravi’s tributary, Jammu Excelsior reports it will create 925 MCM storage for irrigation and power. Chenab’s Ratle project’s dam has a 78.71 MCM capacity, and according to 'The Tribune,' India’s Shahpurkandi dam on Ravi—now operational—helps divert about 1,150 cusecs for irrigation, previously lost to Pakistan.

India's Three-Phase Strategy

Western river projects yield minor joint storage capacity of a few hundred million cubic meters—paling compared to extensive eastern river infraructures like Bhakra, Pong, and Ranjit Sagar, enabling India’s use of nearly 95% of its 33 MAF share through large reservoirs. With current setups, India can store or channel only a portion of westward Indus System water.

Coming Out of the Agreement: An Option

This statement surfaced a day after Jal Shakti Ministry’s Secretary Debashree Mukherjee wrote to Pakistani counterparts, emphasizing India’s longstanding pleas for treaty revisions in light of growing energy demand and population, yet met with Pakistan’s persistent refusals.

Strategic experts like Brahma Chellaney entertain a further alternative with the Indus Water Treaty. Chellaney tweeted Friday, 'Legally, India can exit the treaty. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Article 60, allows suspension or withdrawal due to a material breach by another party.'

India Can Seek Terms Revisions

India’s position clarifies that if exiting remains unchosen, it shall definitely reevaluate and negotiate treaty terms. Central government’s project plans face lengthy timelines of 5-10 years, given complex terrain, funding channels, and environmental approvals challenges. India’s latest Himalaya-bound projects like Kishanganga, Pakal Dul, and Nimoo Bazgo each required 5-11 years to complete.

Source: aajtak

In the upstream case of Indus basin rivers, India holds substantial control over system flows directly affecting Pakistan. Monsoon seasons prompt India to release excess water, which may also pose drought threats to Pakistan if India withholds flows for domestic needs.

Suspending the Indus Water Treaty not only sends a robust signal, but also opens long-term infrastructure opportunities for India, enhancing its control over the Indus System—critical as 25% of Pakistan's GDP relies on this—meeting growing domestic water and energy needs.