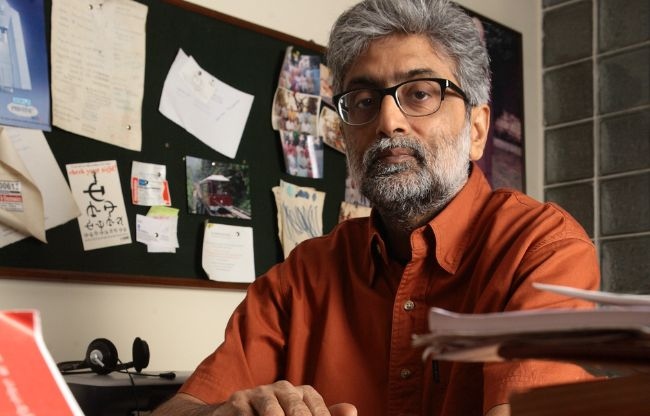

The Supreme Court delivered a significant blow to activist Gautam Navlakha, asking him to clear a debt of 1.64 crore INR to the NIA. This amount stems from the expenses incurred during his house arrest period.

The NIA has demanded Navlakha reimburse these costs. In response, a Supreme Court bench led by Justices M.M. Sundresh and S.V.N. Bhatti declared, 'If you have requested house arrest, you must also bear the expenses incurred.'

The apex court maintained, 'If you have sought this arrangement, then the payment is also your responsibility. You cannot evade this, as it was at your behest.'

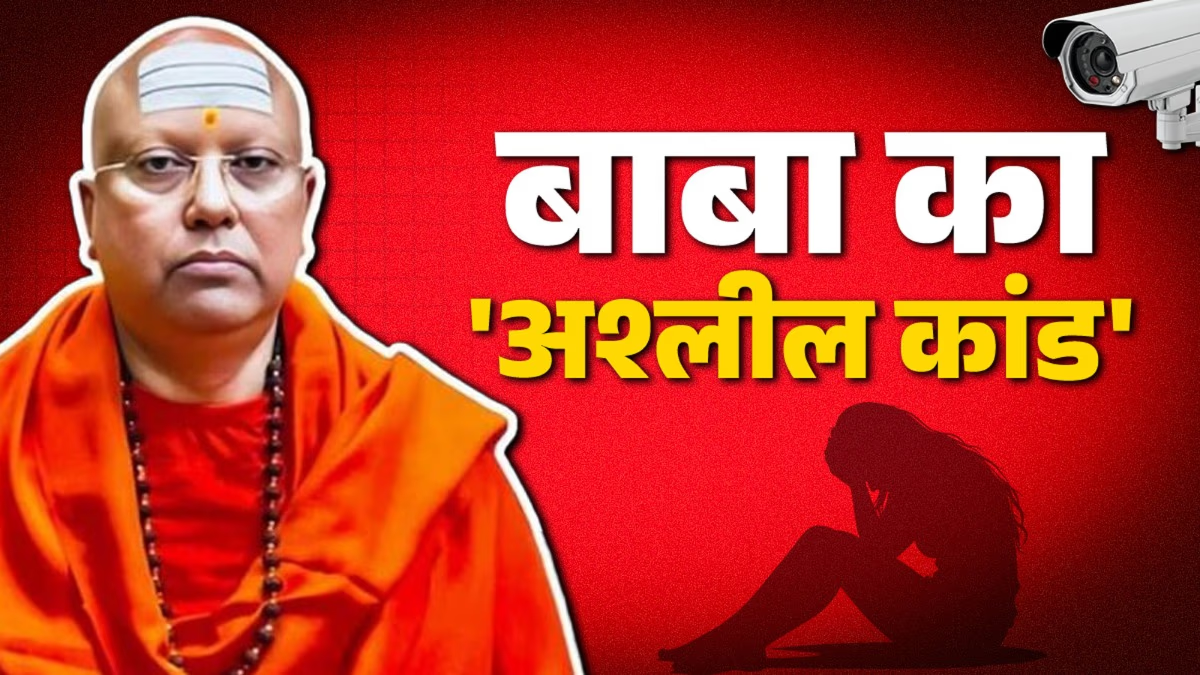

Navlakha, implicated in the January 2018 Bhima Koregaon violence in Maharashtra, was arrested in August 2018. Since November 2022, he was under house arrest in Mumbai.

However, it's noteworthy that Indian law does not have specific provisions for 'house arrest'. In May 2021, the Supreme Court had indicated that in special circumstances, courts could order house arrest under Section 167 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC).

What Exactly is House Arrest?

House arrest confines an accused to their residence. Police are stationed around the clock outside the home. During this period, the accused is subjected to several constraints, essentially turning their home into a makeshift prison.

There are various terms associated with house arrest. When the Supreme Court allowed Navlakha house arrest in November 2022, several restrictions were imposed.

Navlakha was confined to a 1BHK apartment in Mumbai. The police would be present outside his home constantly. CCTV cameras were installed outside his room and at the entry and exit points of his house. He was permitted to leave the house for walks, but even then, he was accompanied by the police and was not allowed to communicate with others.

He was granted the privilege to make a phone call once a day for ten minutes under police supervision. Nonetheless, he was allowed to watch TV and read newspapers. Two family members were also allowed to visit him weekly for a maximum of three hours.

Source: aajtak

What are the House Arrest Rules?

In India, house arrest is recognized as 'preventive detention'. Certain provisions within Section 5 of the National Security Act address this. It suggests that instead of jail custody, an accused can be considered for detention at another appropriate location determined by the government.

In May 2021, the Supreme Court, led by Justices U.U. Lalit and K.M. Joseph, stated in their ruling that custody under Section 167 of the CrPC is typically interpreted as police or judicial custody. However, courts have the discretion to order house arrest in special cases.

When is House Arrest Permitted?

Before imposing house arrest, the Supreme Court emphasized that factors such as the accused's age, health, behavior, and the severity of the crime must be considered.

On November 10, 2022, when the Supreme Court decided to place Navlakha under house arrest, their rationale was, 'He is an elderly man of 70 years. It is uncertain how long he will live. We are not granting him bail; we are merely providing house arrest as an option.'

The Court had previously noted that promoting the use of house arrest could alleviate overcrowding in prisons and reduce costs spent on inmates.

This decision also mentioned that in view of the increasing jail population, magistrates or courts could grant house arrest to accused individuals under Section 167 of the CrPC, suggesting that dangerous inmates may be the only ones retained in prisons going forward.

Source: aajtak

Is House Arrest Similar to Bail?

Article 21 of the Constitution guarantees liberty as a fundamental right to every Indian citizen. When an accused files a bail petition, it also falls within the ambit of Article 21, as the right to live freely is a given.

In May 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that the right to bail is a fundamental right under Article 21, inherently connected to liberty.

However, the court clarified that bail and house arrest are different. The government argued that permitting house arrest is tantamount to releasing the accused on bail.

The apex court countered, stating that house arrest does not guarantee freedom for the accused; it is a form of custody with imposed restrictions, distinct from police custody.

Can an Accused Demand House Arrest?

Under Section 41 of the CrPC, in cases of cognizable offenses, the police have the authority to arrest individuals without a warrant. Nonetheless, according to Section 57 of the CrPC, the accused must be presented to a magistrate within 24 hours of the arrest.

As per Section 167 of the CrPC, the magistrate may order the accused to be held in police custody for a maximum of 15 days, transitioning to judicial custody thereafter. In cases under the UAPA, this custody period can extend up to 30 days.

Under Section 167 (2), an accused can petition for bail. The court then decides to grant bail or detain the accused.

It is not explicitly stated whether an accused can request house arrest. Whether to place an accused under house arrest is at the discretion of the court. However, as clarified by the Supreme Court in its May 2021 ruling, courts can issue house arrest orders in certain cases under Section 167.

Source: aajtak