Recently, there has been a significant uproar over the toxic waste of Union Carbide following the Bhopal gas tragedy. The chemical waste was relocated from Bhopal to Pithampur for incineration, sparking outrage among locals who vehemently opposed its disposal. Despite experts providing logic that the waste was non-toxic now, the public remained steadfast in their resistance.

This scenario reflects only one state's predicament, unwilling to accept chemical waste from one part to another. Yet, there exists a nation willing to accumulate highly toxic nuclear waste from around the world.

In 2002, Kazakhstan gave the green light for countries worldwide to deposit their accumulated nuclear waste within its borders. Split from Russia in the nineties, this Central Asian nation faced dire economic needs. This agreement between Western countries and Kazakhstan's government mirrored that of a desperate youth selling a kidney to an affluent family for financial relief.

Was it just financial necessity, or was there more to the consent?

Three decades ago, Kazakhstan severed from the Soviet Union, attaining freedom but lacking in celebratory resources. Its economy revolved around Russia, and with Russia's absence, it plummeted by 40% within a mere five years of independence.

Transitioning from the ruble to its currency, the tenge, the country struggled with continuous economic decline despite numerous efforts. Kazakhstan possessed oil, uranium, and various minerals; however, funds and expertise for extraction were nonexistent.

Source: aajtak

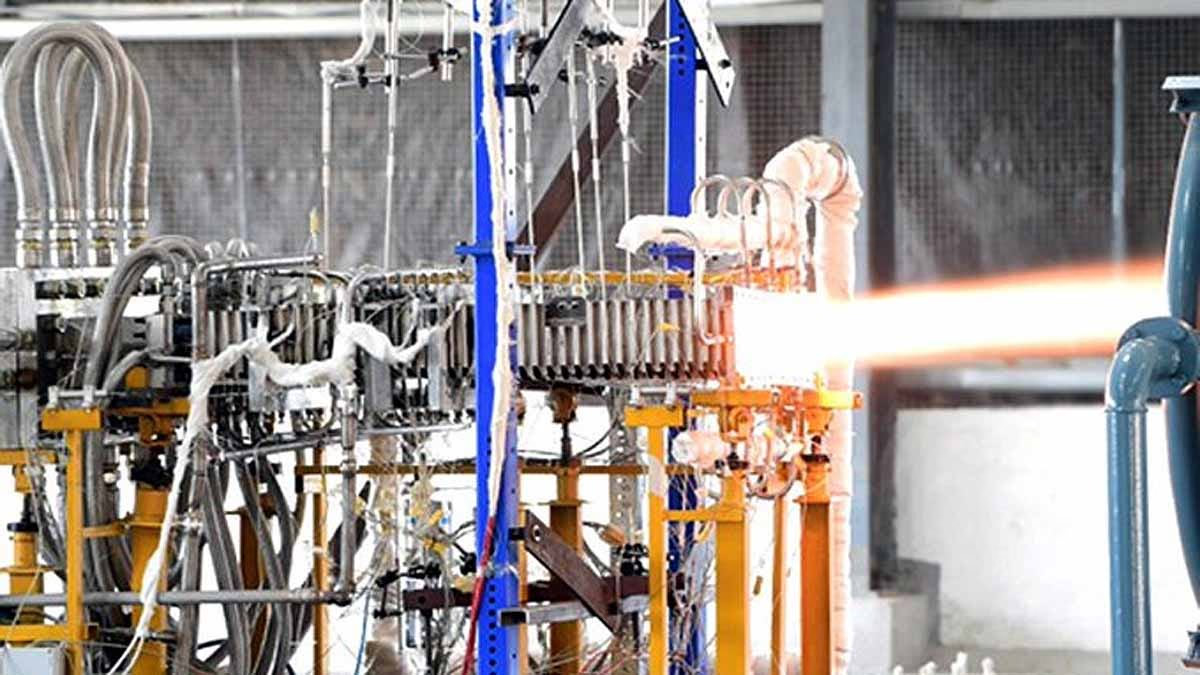

The first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, tirelessly worked on the economy when an intriguing proposal emerged—the Nuclear Waste Dumping Initiative. Under this agreement, nations manufacturing nuclear weapons proposed conducting tests but sending the resultant waste to Kazakhstan. This proposal surfaced collectively from American and European countries.

Why not manage the waste domestically?

Decommissioning nuclear waste posed enormous risks, potentially contaminating soil, water, and air, directly affecting populations and the environment. Consequently, Western nations were opposed to annihilating nuclear waste within their territories, contemplating outsourcing to avoid local uproar. Kazakhstan seemed ideal, a vast expanse with sparse population.

Another Reason

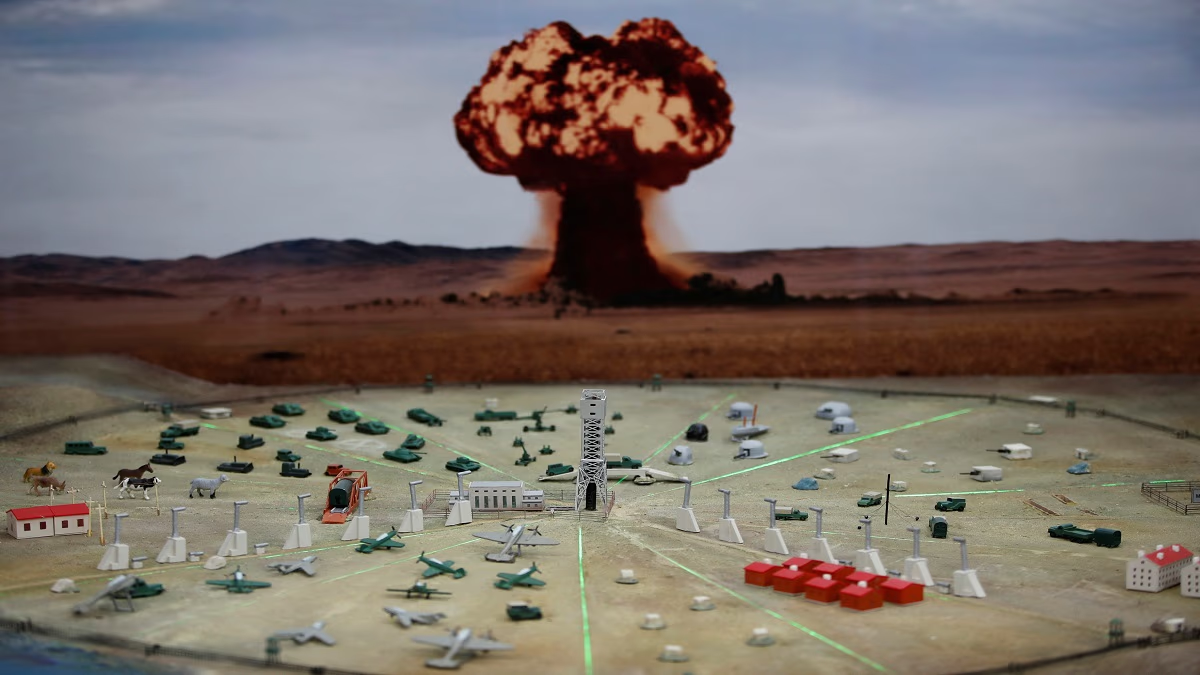

During Soviet rule, Kazakhstan underwent numerous nuclear tests, particularly in the Semipalatinsk (now Semey) region, from 1949 to 1989, with the soil rendered useless and barren. Upon independence, although Kazakhstan retained a nuclear arsenal, the then-president opted for its surrender, earning accolades internationally but inviting a peculiar form of insecurity.

Source: aajtak

Economic Gain Enticed the Nation

Financially driven and militarily weakened, Kazakhstan considered Western nations’ proposal of hosting their toxic waste alluring. The argument was simple: tests had precedently occurred there. In return, Kazakhstan was promised billions in financial aid and investment, initially focusing on funds for storage. This agreement appeared feasible to Kazakhstan’s administration.

Public and Organizational Resistance Arose

Within mere months, the public became aware of potentially becoming global nuclear waste recipients. As the plan unfolded, opposition sprouted from people and environmental groups, branding it economic blackmail—an inequitably potent truth. The impoverishment allowed affluent countries to propose their onerous strategy.

With time, Kazakhstan’s government realized an official nod to the proposal could spark national discontent and destabilize the fresh, unblemished free nation. Ultimately, in 1998, the proposal faced formal rejection.

Source: aajtak

Current State of the Former Nuclear Testing Ground

In Semipalatinsk, more than 450 nuclear tests occurred from 1949 over four decades, including over a hundred above-ground tests. This left a vast area of over ten thousand square kilometers contaminated with radioactive emissions, affecting this locale’s air, water, and soil to date. The barren land offers limited opportunities for agriculture or livestock rearing, while the lakes and rivers also remain tainted, affecting humans.

Radiation exposure has left lingering effects, with cancer, skin ailments, and congenital diseases being commonplace. Despite testing having ceased years ago, impacts persist among local inhabitants and successive generations. This progressive issue contributes to the area’s decreasing population, notable immediately post-independence, as residents opted for relocation to elsewhere within the country. When compared to Soviet era numbers, current residency has stagnated.

Where is the US and Europe’s Nuclear Waste Now?

With the proposal dismissed, powerful nations devised separate strategies. The US maintains several temporary storages for the toxic waste, albeit constrained by capacity over the long term. In the nineties, the US proposed a similar dumping strategy within a state, thwarted by subsequent disputes. Europe embarks on multiple projects addressing nuclear waste disposal.