In the third chapter of the history of terror in Kashmir, we take you back to that winter of 1989 when the blood of Kashmiris was spilled and independent India witnessed its largest exodus.

Al-Safa is one of the two hills in Mecca where Muslims perform a sacred ritual during the Hajj. But for Kashmiri Pandits, Safa (meaning pure) became synonymous with a dreadful morning.

Winters in Srinagar see the sun only briefly. In Persian, it is referred to as Aftab. Its light falls over Dal Lake around noon and then hides behind the Zabarwan hills soon after.

Source: aajtak

But the morning of January 4, 1990, was even darker. It was the most ominous and horrifying morning in Srinagar's history.

The morning newspapers, Al-Safa and Aftab, carried a frightening warning on their front pages. This warning was for the Kashmiri Pandits—those whose ancestors, Hindu priests and scholars, had settled in the valley three thousand years ago. The warning stated:

'Leave, this is the land of Islam.'

This decree came from Hizbul Mujahideen, a newly-formed terrorist organization receiving assistance from Pakistan, which had already sowed an atmosphere of fear with targeted killings.

However, most Pandits did not take it seriously, as they had endured centuries of persecution under Islamic rulers and remained firm on their land. They believed they were entirely safe on their ancestral land.

Source: aajtak

The Curse of History

It is believed that the name of the Kashmir Valley was derived from sage Kashyap. Until the 14th century, this region was a hub of Hindu and Buddhist religions. Several waves of Islam touched down but either couldn't affect the valley or were thwarted by the Hindu Shahi rulers of Gandhara. This kingdom shared robust ties with Kashmir, especially during the reign of Queen Didda of the Lohara dynasty (924-1003).

The first wave of Islam entered quietly when a Tibetan prince, Rinchan, seized power in Kashmir and embraced Islam under the influence of Sufi saint Bulbul Shah. Following Rinchan, Shah Mir rose to power, imprisoning Rinchan's son and wife while establishing Islamic rule himself. This marked the onset of forced or lured religious conversions. Some converted for social standing, others for land and rewards, and some out of fear.

Source: aajtak

By the time the sixth ruler of this dynasty, Sikandar Shah, also known as 'The Idol Breaker,' died in 1413, about 60% of the population in the valley had embraced Islam.

Within the Hindu population, the Brahmins made up the largest portion. According to historians, Brahmins played three significant roles in the valley—as priests, astrologers, and officials (government employees).

Disillusioned by Sikandar Shah's persecutions, many Kashmiri Brahmins migrated to the plains of Jammu or other states. They were welcomed there for their scholarship, education, and administrative skills, earning both prestige and position.

Even after converting, many new Muslims couldn't completely sever their ties with their lineage and family traditions. There were minor changes in names, but roots persisted. For instance, Bhat, Dhar, and traders (Vaṇija) became Bhat, Dar, and Wani. The faith changed, but a new form of ethnic identity emerged, offering a new place but erasing the past.

Source: aajtak

History sometimes plays cruel jokes. Once, the Hindu Shahi rulers of Gandhara laid down their lives fighting Mahmud Ghaznavi to protect India from invasion. But their descendants today form part of Pakistan's Janjua clan, Muslims preparing to launch their Ghaznavi missiles at the same India. A similar tragic history was repeating itself, this time in Kashmir.

Friends Turned Foes

It was the morning of September 14. Famous lawyer and Kashmiri Pandit Tikalal Taploo was on his way to High Court. He stopped to talk to a weeping young girl close to his home. But suddenly, two masked men appeared, shooting him three times. Taploo died on the spot. Later it was revealed that one of the assailants was Javed Ahmed Mir 'Nal ka', an active member of the JKLF (Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front). Following this, a wave of murders commenced.

On November 4, Justice Neelkanth Ganjoo was shot dead. He had sentenced Maqbool Bhat to death in 1966 for the murder of a CID inspector. Terrorists were trailing him ever since he returned from Delhi. They cornered him in a crowded Srinagar market and executed him.

Source: aajtak

On December 27, Prem Nath Bhat, a journalist and lawyer, was dragged out of his Anantnag home. Masked terrorists filled his chest with bullets. Blood spread everywhere, leaving a message—fear and intimidation for the few Pandits left in South Kashmir.

At least six terrorist groups were active in Srinagar that winter. Yet, the majority of murders were traced back to the JKLF, founded by Amanullah Khan with Pakistani ISI's support. The most notorious terrorist from this organization was Farooq Ahmed Dar, aka Bitta Karate. He confessed to killing at least 20 Pandits on instructions from the ISI's top commander Ashfaq Ahmed Wani between 1989 and 1990.

These targeted killings were the precursors to the hysteria that gradually devolved into a frenzy of cruelty.

A Dismantled Community

Twists in history never allowed Kashmiri Pandits to live in peace even on their own land. Under successive Muslim rulers and the Mughal Empire, their population dwindled to less than 15%. Then, even under Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Sikh Empire, there was little protection extended to them, leading to their emigration from the valley by the mid-19th century.

A respite arrived with the Dogra regime when Gulab Singh bought Kashmir from the British for 7.5 million Nanakshaw rupees in the aftermath of the British-Sikh war. Under Dogra rule, the Hindu population in the valley stabilized between 5-6%

A short period of relief came during the Dogra rule, when Gulab Singh purchased Kashmir from the British for 7.5 million nanakshahi rupees after the Anglo-Sikh war. During Dogra's reign, the Hindu population in the valley stabilized between 5-6%.

However, another exodus followed post the 1947-48 Indo-Pak war, where Pakistan occupied a large portion of Kashmir.

Source: aajtak

In 1951, land reforms limited ownership, prompting many Pandits to leave the valley. By the 1990s, the Pandit population had shrunk to less than four percent—about 150,000 people (extrapolated from the 1981 census).

Now, separatist forces were plotting to annihilate even this small community—along with the shared legacy that had characterized the valley for centuries.

Convert, Flee, or Die

The warning received on January 4 paralyzed Srinagar with fear and silence among the Kashmiri Pandits. Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah's National Conference government was already shaky, looking exhausted and ineffective, neither trustworthy nor powerful. On January 18, 1990, Farooq Abdullah learned of Jagmohan—considered an adversary by Abdullah and who had served as governor from 1984 to 1989—being reinstated as governor. The V.P. Singh government had decided to send him back to manage the situation.

In anger and protest, Farooq Abdullah immediately resigned. His departure created a vacuum of power, which became a golden opportunity for terrorists, and they seized every chance to capitalize on it.

Source: aajtak

The Night When Srinagar Trembled

By the evening of January 19, 1990, Srinagar turned into a frenzied spectacle. At 9 PM, speakers from mosques across the valley began spewing venomous slogans.

The cold air echoed with pre-recorded chants:

'If you live in Kashmir, you will say Allah-O-Akbar.' 'What will work here? Mustafa's regime.' 'We want Pakistan—with Pandit women, without their men.'

By 9:30 PM, the chants had evolved into a booming terror. Every Pandit household locked its doors and windows, families huddled in corners—every footstep froze their hearts, every moment felt like impending doom.

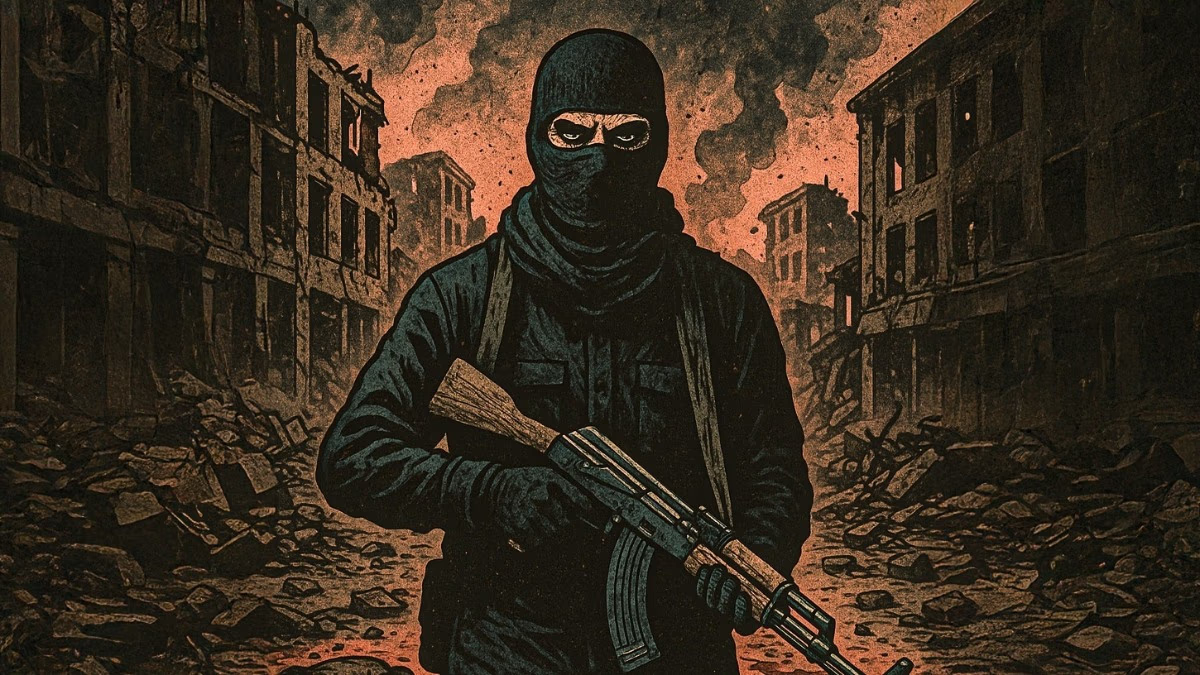

Outside, masked men wielding Kalashnikovs roamed the streets, pasting posters on walls and marking Pandit homes with red paint.

The decrees were clear—adopt Islamic attire, forsake alcohol, close cinemas, and adjust watches to Pakistan’s time. Convert to Islam, leave the valley, or prepare to die.

Police were nowhere to be found. The administration seemed to have vanished. There was no sign of the army. Phones went unanswered. Cries for help disappeared into the cold night air.

Source: aajtak

As Pandits huddled in fear, another rising storm brewed outside. The predominantly Muslim population had taken to the streets, thousands strong shouting slogans:

'Indian dogs go back!' 'What does Azadi mean? There is no god but Allah!' Mosques urged people—'Rise for the last time, break free from India's shackles.'

India Today described this night as 'an open rebellion,' a direct challenge to India’s authority and legitimacy.

The Morning of Exodus

By midnight, Pandits had come to realize it was no longer possible to stay. Slowly, they packed their bags, balancing what to take and what to leave, decisions made through tears.

The next morning, they began leaving the valley en masse, leaving behind centuries of memories, dreams, homes, orchards—all to predators ready to devour them.

In the months that followed, about 100,000 to 150,000 Kashmiri Pandits—almost the entire community—fled the valley. Some sought refuge in camps, others settled in distant cities where they rebuilt their lives anew.

Source: aajtak

According to the Kashmiri Pandit Sangharsh Samiti, between 1990 and 2011, 399 Pandits were killed, three-quarters of these deaths occurring in 1990. Each name narrates a story of brutality: Lassa Kaul was shot on February 13. B.K. Ganjoo was found hiding in a rice drum on March 19 and was executed there. Sarwanand Kaul Premi and his son were hanged on April 29, their eyes gouged out. Girija Tickoo was gang-raped and cut alive with a saw on June 4.

In the streets, crowds continued demonstrating, hoping for India's defeat. On January 21, near the Gowkadal bridge close to Lal Chowk, anger erupted. The CRPF opened fire on the crowd, resulting in 25 to 55 fatalities—some shot, others drowned in the Jhelum.

The Kashmir valley, consumed by violence and vengeance, increasingly became entrapped in a cycle of terror and repression.