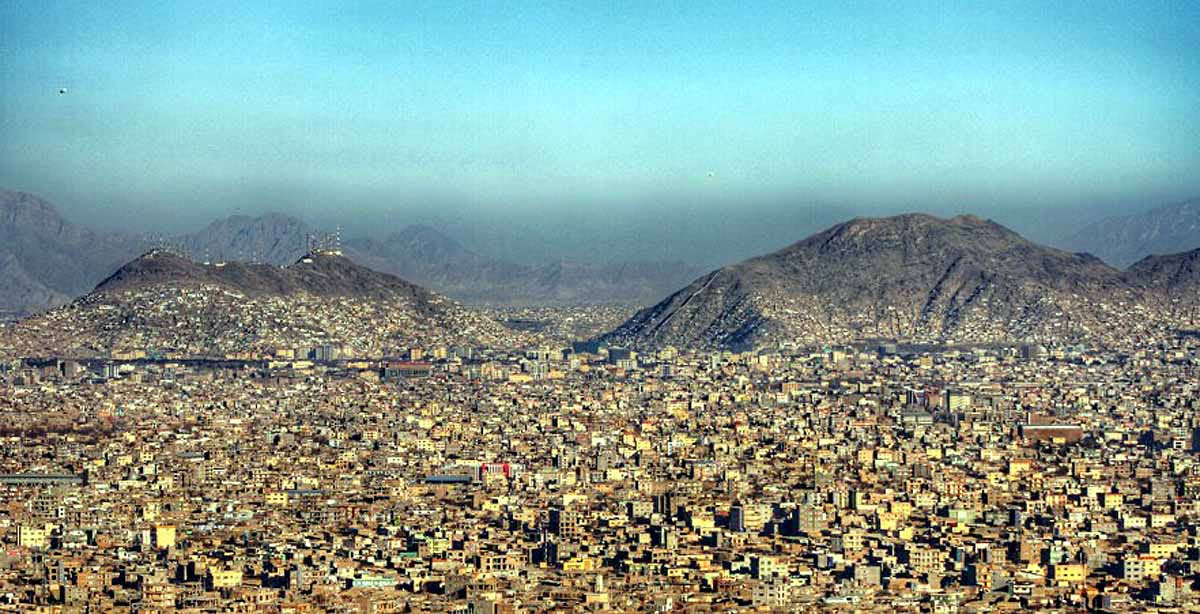

Afghanistan's capital, Kabul, is on the brink of a severe water crisis. A new report indicates that if circumstances don't improve, Kabul could become the first capital in the world to entirely run out of water by 2030.

Due to over-extraction, climate change, and poor management, Kabul's aquifers are depleting rapidly. This could lead to millions of people becoming homeless.

UNICEF and Mercy Corps report warns that if swift action isn't taken, the crisis will not just lead to water scarcity but also pose significant threats to health, economy, and create a humanitarian disaster.

Source: aajtak

What is causing this crisis?

Kabul, a city with a population of 6 million, is entirely reliant on groundwater, sourced from the melting snow and glaciers of the Hindu Kush mountains. However, due to several factors, this water supply has been rapidly dwindling. According to Mercy Corps...

Excessive Water Usage: Kabul extracts 44 million cubic meters more water annually than nature can replenish, depleting its water reserves without any plans for replenishment.

Dried Aquifers: Kabul's aquifers have receded 25-30 meters in the past decade. Half of the city's borewells have already run dry.

Contaminated Supply: 80% of Kabul's groundwater is polluted with dangerous chemicals like sewage, arsenic, and nitrates, posing significant health risks, especially to children and the elderly.

Closure of Schools and Hospitals: The scarcity of clean water has forced the shutdown of schools and health centers in several areas of Kabul.

UNICEF warns that if the current state persists, Kabul could run dry by 2030, potentially rendering 3 million people homeless.

The Roots of the Crisis

The water crisis in Kabul arises from interconnected factors. Let's explore these...

Climate Change

Kabul's water source is the snow and glaciers of the Hindu Kush mountains. However, droughts and reduced snowfall from 2021-2024 have dried up these sources.

Water expert Najibullah Sade says that although rainfall occurs, snowfall is less frequent. Snow provides gradual water release, while rainwater rushes away, leading to unmanaged flooding in the city.

The 2023-24 winter brought Kabul only 45-60% of typical rainfall, limiting aquifer recharge opportunities.

Source: aajtak

Population Pressure

In 2001, Kabul housed less than a million people. After the Taliban left, people flocked to Kabul seeking security and jobs, ballooning the population to 6 million.

Such a large populace has escalated water demand. 120,000 unregulated borewells and hundreds of factories and greenhouses draw billions of liters annually.

Poor Management

A robust water supply system doesn’t exist in Kabul. Only 20% of homes receive water through government pipelines. The rest depend on borewells or tankers.

Reservoirs like Qargha Dam and Shah-Wa-Arous Dam are outdated and clogged with sediment, impairing functionality.

Four decades of war and instability have ravaged water infrastructure. Previous governments and now the Taliban have failed to address this.

Political Instability and Funding Shortfalls

Post-2021 Taliban ascension, western aid to Afghanistan was halted. $3 billion in water and sanitation funding (WASH) was frozen.

USAID reduced funding in 2025, stalling water projects. Required funding was $264 million, but only $8 million was provided.

Major projects like the Panjshir River pipeline and Shahatoot Dam, capable of alleviating Kabul's crisis, are stalled due to financing gaps and Taliban's international isolation.

Source: aajtak

Exploitation by Private Companies

Some private companies are exploiting Kabul's water crisis, extracting public groundwater and selling it at 1000 Afghanis (around 1200 INR), a price hike from the previous 500 Afghanis.

Companies like Alokozy extract 1 billion liters annually, while greenhouses draw 4 billion liters.

Impact on Residents

Kabul’s residents are severely affected by this crisis...

Economic Burden:

People spend 15-30% of their earnings on purchasing water. Some families have taken loans at 15-20% interest for water.

Health Crisis:

Contaminated water has led to an increase in diarrhea, cholera, and other diseases among children. The closure of schools and hospitals exacerbates the situation.

Challenges for Women:

Taliban rules force women to fetch water with a male companion, complicating access. A 22-year-old woman reported fears of harassment while getting water.

Displacement Risk:

If water depletes, 3 million people could be displaced from Kabul.

Efforts and Future Actions

Some efforts are underway, but these are insufficient...

UNICEF and ICRC run small projects, repairing 1315 handpumps and installing 1888 bio-sand filters to cleanse water.

The Panjshir River pipeline, a 200 km project, could supply 100 million cubic meters to Kabul but requires $170 million.

The Shahatoot Dam could be completed by 2027, providing water to 2 million people, if $236 million funding is met.

Solar-powered wells have been introduced in some areas but cannot meet the city’s entire demand.

Suggested Measures

The report recommends several actions...

Stop Water Wastage: Implement regulations on unregulated borewells and control consumption.

Construct New Reservoirs: Build check dams and water reservoirs to recharge aquifers.

Upgrade Old Pipelines: Modernize existing infrastructure to prevent water leaks.

International Aid: Boost humanitarian aid focusing on water despite political issues.

Combat Climate Change: Protect the Himalayas, crucial for snow and rainfall preservation.

Water expert Abdul Basit Rahmani says the crisis can be resolved in 18 months with political will. Cooperation between the Taliban and international community is needed.

Kabul's plight serves as a warning. It could be the first capital to empty its water reserves, driving epidemics, poverty, and economic distress. Countries like India could learn from Kabul’s situation. If solved, groundbreaking projects like Panjshir pipeline and Shahatoot Dam could set a precedent for other cities.