India is a country where the threat of earthquakes lurks in every corner. On November 28, 2025, the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) revised the country's seismic zone map. This new map is a component of the seismic-resistant design code, IS 1893 (2025). The older maps defined zones based on historical earthquake epicenters, but the updated map is constructed with more scientific precision.

The entire Himalayan region is now designated as the most dangerous Zone VI for the first time. This shift places 61% of the nation under medium to high-risk zones. Let's delve into the making of this map, the number of zones, the reasons behind adding a new zone, the removal of Zone 1, and the impact on India.

Read more:

The story of India's earthquake zone map dates back to 1935 when the Geological Survey of India (GSI) crafted the first map following the major 1934 earthquake. It classified the nation into just three zones – severe, light, and minor threats. These maps were based on narratives of earthquake destruction.

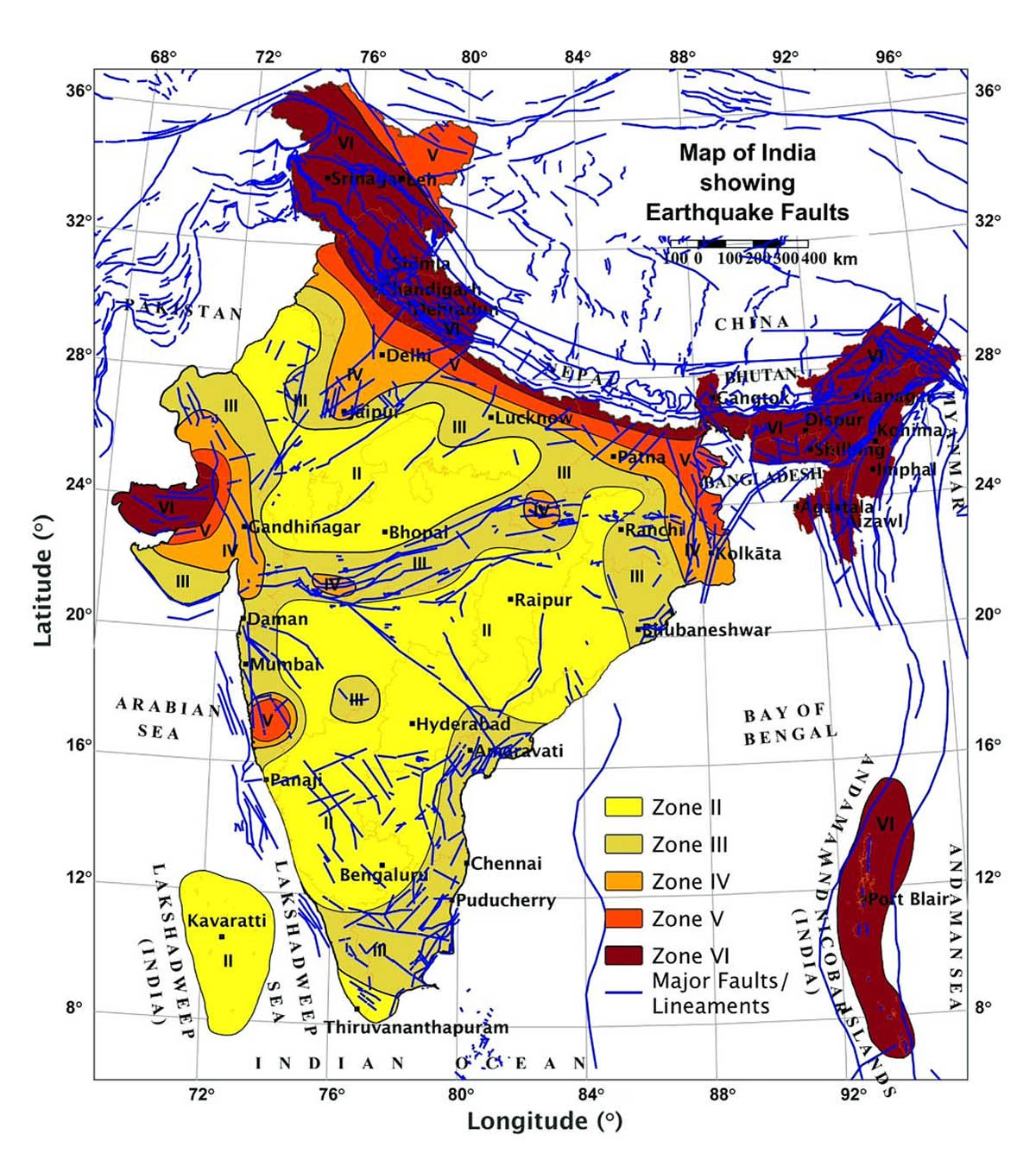

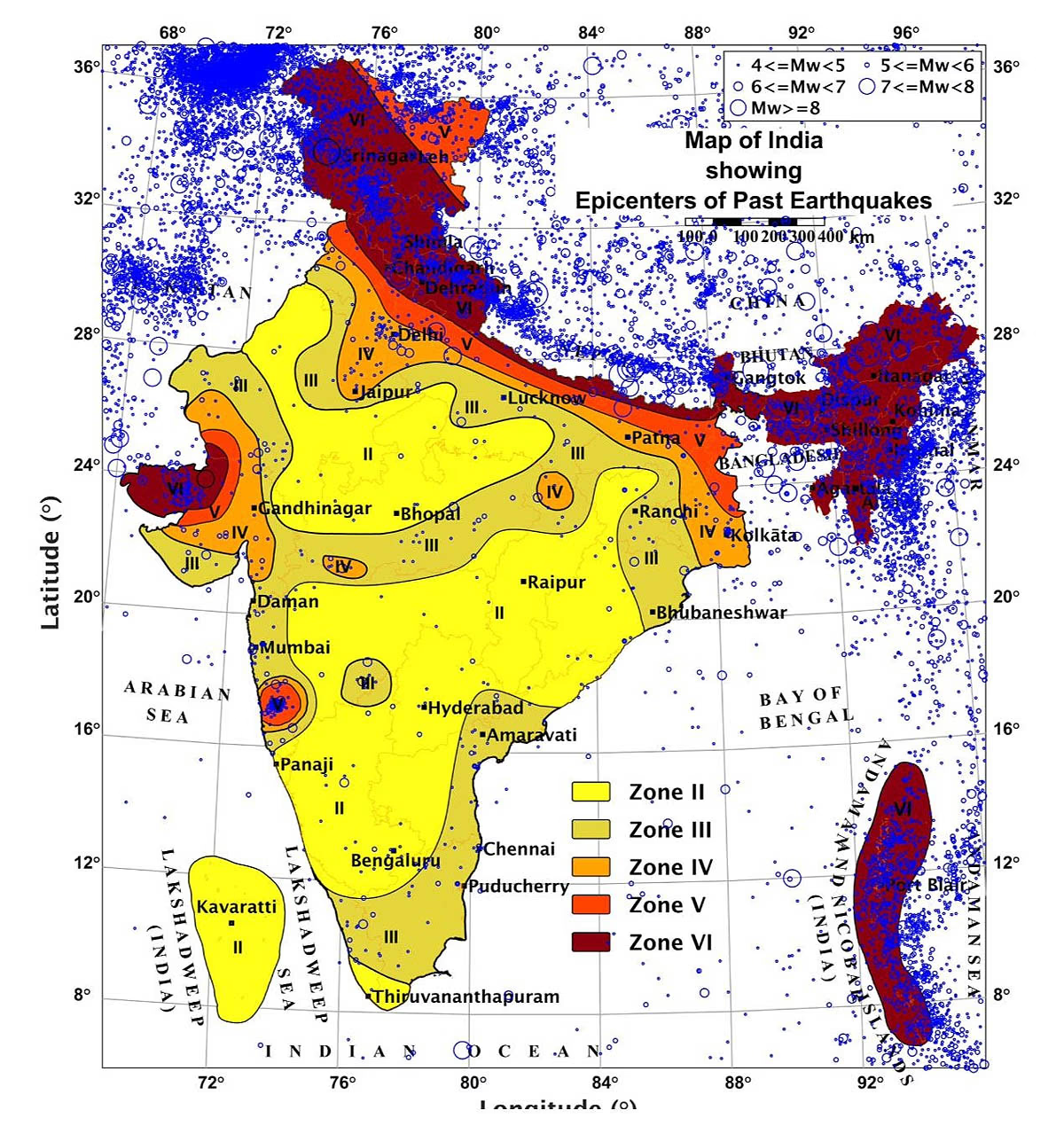

In 1962, BIS expanded it into six zones, seven in 1966, and finally five zones (I to V) by 1970. These were also grounded in historical earthquake centers, soil characteristics, and damage reports. However, these maps became outdated over time, ushering in the need for a scientifically developed map.

Source: aajtak

Termed the Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Assessment (PSHA), scientists estimate the largest potential earthquake within a 50-year, 2.5% probability using computational models. This includes:

Maximum earthquake intensity (magnitude).

Data on soil, rocks, and past earthquakes.

Details of active fault lines (geological fractures).

Intensity of ground shaking (peak ground acceleration or PGA).

Movement of tectonic plates (the Indian plate shifts north by 5 cm annually).

Previous maps altered zones around cities or factories, but the new map is grounded in actual fault strength. It includes an exposure window assessing population density and economic vulnerability, indicating risks to both people and structures. The map is color-coded – green being less hazardous and red indicating higher risk.

Read more:

Zone-6... Agartala, Bhuj, Chandigarh, Darjeeling, Leh, Mandi, Panchkula, Shimla, Shillong

Zone-5... Ambala, Amritsar, Bahraich, Jalandhar, Karnal, Saharanpur, Rampur

Zone-4... Noida, Delhi, Gurugram, Ghaziabad

The older maps (2002 and 2016) contained four zones – II, III, IV, and V, with Zone II being the least hazardous and Zone V the most. However, the 2025 map appreciates five zones: II, III, IV, V, and the new Zone VI.

Zone II: Minimal threat (11% of the land), parts of southern India.

Zone III: Moderate risk (30% of the land), central India.

Zone IV: High risk (18% of the land), major cities like Delhi, Mumbai.

Zone V: Very high risk (11% of the land), Kutch in Gujarat, Northeast India.

Zone VI: Extreme risk (new), entire Himalayas from Jammu-Kashmir to Arunachal.

Now, with 61% of the land under the medium-high zone category, cities straddling zone boundaries are reclassified into higher zones to avoid underestimation of risk.

Source: aajtak

Previously, the Himalayas were segmented into Zones IV and V, which was incorrect. The Himalayas formed from the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates, where pressure escalates annually. Main faults – the Main Frontal Thrust and the Main Boundary Thrust – have maintained seismic gaps (regions of earthquake inactivity) for centuries. No significant earthquake has hit central Himalayas for 200 years, implying energy accumulation.

Zone VI was established because PSHA revealed potential for greater seismic intensity in the Himalayas. Ruptures in outer Himalayan faults could extend tremors southward, as far as Dehradun. Older maps were built on administrative borders, new ones on geological realities. Experts claim this revision addresses decades of inaccuracies.

Zone 1 was dismissed in 2002 (and remains so in 2025). In early maps (1962-1970), Zone 1 signified "no risk," but scientists asserted that seismic events are possible everywhere on Earth. The zero-risk zone was scientifically flawed. Thus, Zone 1 was merged into Zone II. No place is deemed absolutely safe – all areas require minimal preparations. This adjustment came post the 1967 Koynanagar earthquake, which demonstrated even supposedly safe areas could be shaken.

Read more:

This new map is a major wake-up call for India. Currently, 75% of the population resides in active seismic zones. The rapidly expanding cities (e.g., Delhi, Dehradun) are at higher risk. Key implications include:

Impact on Construction:

All new buildings, bridges, schools, and hospitals must adhere to stringent regulations. Zone VI foundations need 50% more strength, with doubled steel reinforcement. Non-structural elements (like roofs, tanks, elevators) must be anchored if exceeding 1% of their weight. Retrofitting of existing structures becomes mandatory. Minimal changes in southern India, but construction in the Himalayas may cease. Costs could rise by 10-20%, but lives will be safeguarded.

Impact on Safety:

Critical buildings (hospitals, schools) will remain operational post-earthquake. New scrutiny of liquefaction (soil liquefying) and soft soil is mandated. Reclassifying border cities (like Dehradun) into higher zones will shield millions. Disaster management will be enhanced – the NDRF must formulate new plans.

Economic and Social Impact:

With 61% of the land in high zones, urbanization will slow, but safety increases. Annual earthquake damage of 5-7 billion dollars will be mitigated. Farmers, workers, city dwellers will all be affected – but long-term protection of lives and property will be ensured. Himalayan states (Uttarakhand, Himachal) might see a halt in tourism and development, but eco-friendly building will be promoted.