In Uttarakhand's Uttarkashi district on the afternoon of August 5, around 1:30 pm, a tranquil stream known as Kheer Ganga suddenly transformed into a torrent of destruction. The swollen flow carried boulders, debris, and massive volumes of water downstream, wiping out buildings in Dharali's market area and claiming lives.

Rescue operations are ongoing, but the true death toll remains unknown since many bodies lie buried under 40 to 60 feet of debris and boulders. In the meantime, Uttarkashi's disaster control center has received inquiries about over a hundred persons unaccounted for who were in Dharali during the flood.

The flood's trigger remains unclear, yet experts have posited several potential causes.

Avalanches of Ice and Rock

Senior geologist Navin Juyal, with over three decades of experience in Uttarakhand, suggests the disaster originated from a cirque or hanging glacier. Cirque glaciers, resembling shallow amphitheaters, collect ice.

Post the 'Little Ice Age' conclusion in 1850, these glaciers began to retreat, leaving behind loose rock and debris known as moraines, prone to erosion and flow. Juyal estimates that on August 5, Kheer Ganga's feeding cirque glacier experienced a rock and ice avalanche.

Typically, such events result from a cloudburst, yet Juyal thinks otherwise. He proposes that moderate but persistent rainfall triggered the event in the preceding days. Furthermore, snowfall extended into this year's spring, which Juyal attributes to climate change. Springtime snow harbors more moisture than winter snow, exacerbating vulnerabilities.

According to Juyal, 'Continued snowfall until March-April probably led to significant water-laden snow accumulation in the cave-like area fronting Kheer Ganga's cirque glacier. From August 3 to 5, ongoing rain may have overfilled this deposit, causing cracks and collapses, crashing down as ice-rock avalanches into Kheer Ganga.'

Source: aajtak

(Dharali in 2023, before the market became decimated)

Due to steep slopes, this avalanche rapidly descended, sweeping along glacial moraines (boulders, silt, soil). A landslide along the route temporarily halted the flow; once breached, torrents of debris, water, and boulders cascaded into Dharali within seconds.

The calamity mirrors the February 2021 Chamoli district flood, where 204 perished, and two hydropower projects suffered damage. An 80% rock and 20% ice avalanched from Ronti Peak, generating frictional heat, melting ice, and unleashing a torrent of water, slurry, and debris.

Senior geologist Yashpal Sundriyal states, 'The Chamoli flood and Dharali disaster share similarities—an intense slurry flow, loaded with debris and boulders, swept away structures and claimed lives.'

Besides Kheer Ganga, two nearby streams—Harshil Gad and Jhala Gad—also surged on August 5. Near Harshil (around 4 km from Dharali), an Indian Army camp was damaged, and at least nine soldiers went missing. Juyal suspects all three streams, in proximity and emanating from similar geomorphic cirque glacier structures, likely experienced ice-rock events akin to Kheer Gad (Kheer Ganga).

Though media speculation suggested a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) instigated Dharali's disaster, Juyal found no satellite imagery evidence supporting this claim.

Landslide Lake Break Flood

Experts are exploring if Kheer Gad formed a temporary lake en route, which later breached. This might explain the sudden burst and ebb akin to a dam break. Geologist Piyush Rawat theorizes a landslide induced by torrential rain formed a temporary blockage, capturing water. Upon breaching, landslide lake burst flooding ensued.

Locals noted diminished Kheer Gad water levels prior to the flood, suggesting upstream water pooling. However, dense cloud cover frustrated clear satellite imagery acquisition.

Did a Cloudburst Occur?

Post-disaster, Uttarakhand's government attributed Kheer Gad's surge to a cloudburst. Yet, Rawat contends this 'convenient' explanation lacks comprehension. Sundriyal adds, cloudbursts typically unfold on the Himalayas' southern slopes, unlike the northward gradient of Kheer Gad, rendering such events scarce.

Source: aajtak

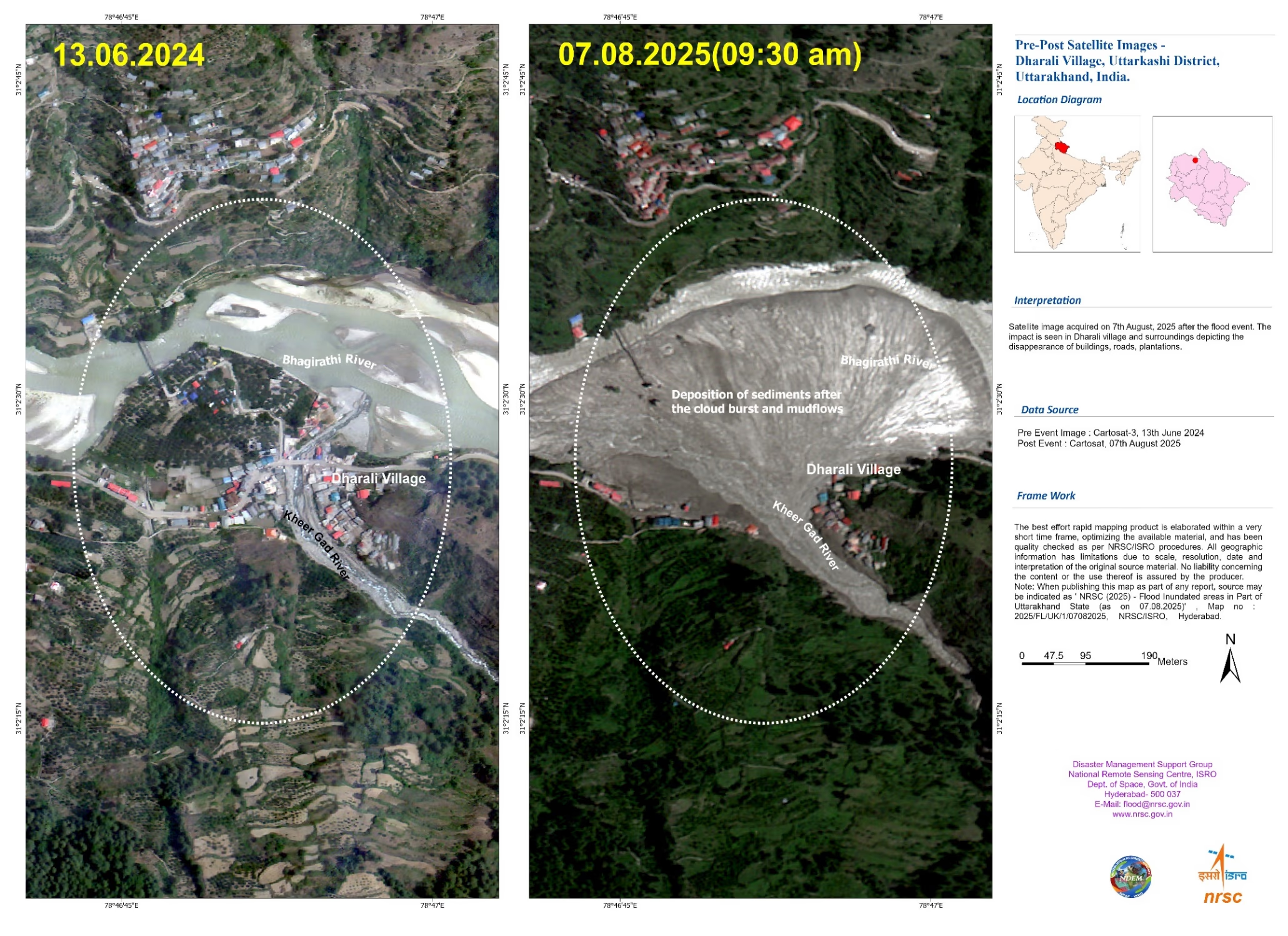

Satellite imagery: Dharali before June 13, 2024, disaster, and post-August 7, 2025 (NRSC, Hyderabad)

According to IMD data, Uttarkashi experienced only light to moderate rainfall from August 3-5, with no stations registering cloudburst signatures. IIT Roorkee's Dr. Ankit Agrawal's team scrutinized the rainfall data from July 24 to August 5. They noted intense storm formations on August 5 yet recorded a peak maximum hour rainfall of 36 mm/hr, well below the 100 mm/hr cloudburst benchmark. Nonetheless, the team has not entirely dismissed the cloudburst hypothesis.

Source: aajtak

The aftermath of Kheer Ganga's 2013 flood at Dharali (courtesy: Chetan Singh Chauhan)

Not Merely a Natural Cataclysm

Kheer Gad has historically instigated floods, notably during the 2013 GLOF incident at Kedarnath Valley, claiming over 4,000 lives, Kheer Gad amassed 4-5 feet of debris in Dharali. Dharali's market area perches atop a debris-flow fan, a flood deposit-induced instable formation. The region's volatility renders it unsuitable for habitats, yet construction has burgeoned over two decades. Sundriyal emphasizes, 'Dharali isn't a safe human settlement terrain. The flood reinstated the river's ancestral course.'