Shivpuri, a verdant city in Madhya Pradesh, might seem like any other middle-tier area at first glance. Its sleepy, smoke-shrouded streets are flanked by old-fashioned shops, while men engage in banter over paan at intersections, and women, with veiled heads, walk by - most transported from regions like Odisha, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Chhattisgarh. These seemingly married women are, in reality, bought over great distances.

Narrow alleys teem with brokers. You specify your needs, and they will arrange a girl. Prices range from a mere 10,000 to several lakhs, with the possibility of resale if not satisfied. To ensure the buyer doesn't land in trouble, a settlement contract is also a part of the deal.

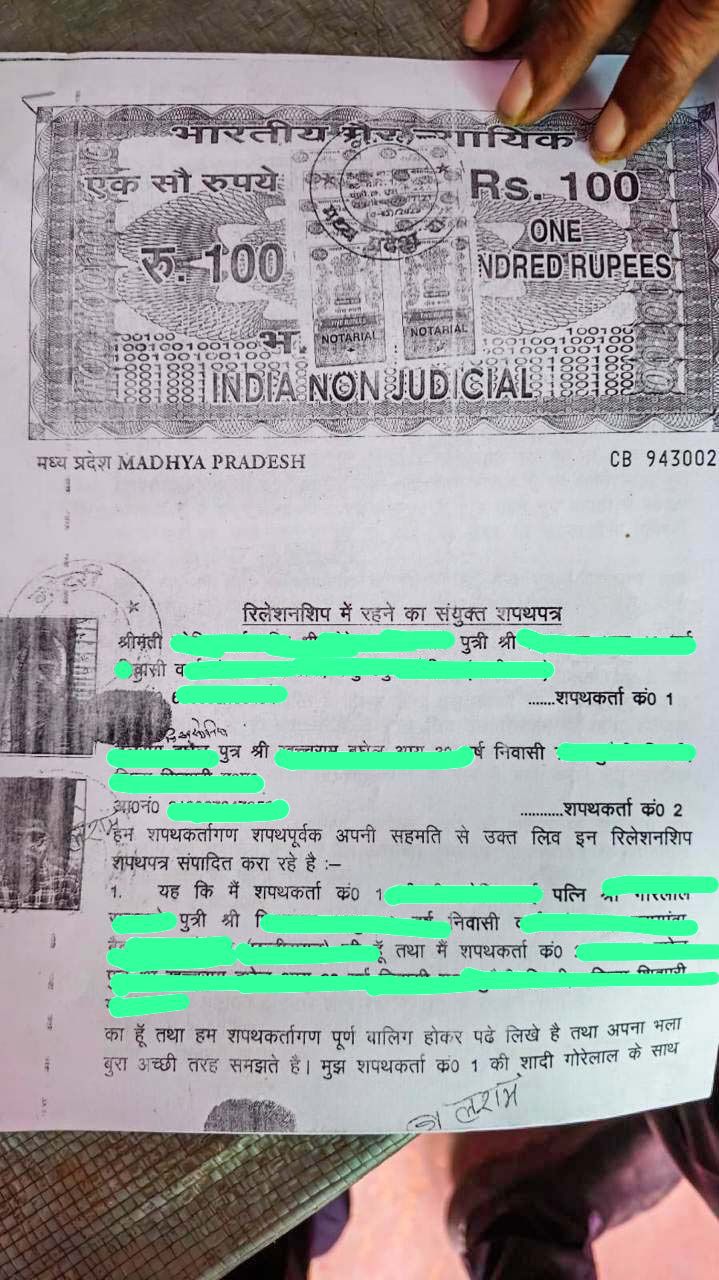

A disturbing tradition called 'Dhadicha', involving paper-based agreements for buying and renting out women, may seem obsolete but lurks behind closed curtains; known by various regional names like Dadhicha, Kharicha, or Ladicha.

Delve deeper and you'll find notaries ready with contracts and brokers to provide you with 'fresh maidservants'. They quickly show photos for selection and promise delivery within a week. The price, however, will vary based on age, looks, and whether the product is 'fresh' or 'used'.

Our journey from Delhi unravels this malignant tradition thriving like an insidious disease. We reached Shivpuri in about 8 hours via the Agra-Bombay National Highway. Our destination was Pohri Tehsil, to meet the trafficked girls and their agents.

Source: aajtak

Some aggrieved husbands who lost their wives to escape also crossed our paths. They express in bitter tones, 'The money's gone. The maid's gone. Had I known she'd flee, I'd have sold her to recover the costs.' But why did the wives flee?

Possibly due to misunderstandings; when one couldn't understand our language, I had to resort to physical reminders. Maybe that's what ticked her off,

he explained with no visible trace of remorse, comparing his lost wife to malfunctioning appliances.

In Pohri Tehsil, with its 250 villages, for every 1000 men, there are only 874 women. The gap between demand and supply is bridged by these agents who traffic girls from impoverished states. A considerable amount of the price goes to the family or intermediaries in other states, while the remainder ends up with the local broker. Occasionally there's a ceremony with garlands, often not even that. The girl arrives and manages all household chores like an old servant; the only difference being, she can never earn trust.

The age gap is often so massive, the fear of the girls fleeing looms large. Yet, there's a remedy: they are impregnated upon arrival - 'She'll surely settle after seeing the face of her child' reasons a local source introducing us to one such face.

Neha, with three children in her four-and-a-half years' stay, was hanging laundry when we arrived. Indifferent to new faces, her eyes devoid of curiosity, she stood up, wiping her hands on her sari when called. Her face, free from questions or surprise, exhibits naive tenderness.

Source: aajtak

'May we talk inside?' I asked. Neha, clad in an old, faded sari, looks on silently. After my repeated requests are met with silence, her mother-in-law takes the lead, suggesting we talk there while she starts the cooler. Declining, I insisted on a private conversation with Neha - for her benefit. Reluctantly, they agreed, sending her to the adjacent room.

Speaking in a blend of Bundeli and Hindi, Neha recounts how after her parents passed away five years prior, intermediaries convinced her sisters to agree to her marriage - 'The family's well-off, though he's slightly lame. For an orphan, what more could you get?' She shrugged, dismissing the question.

Your marriage wasn't official then?

'No. They garlanded me, stuffed a sweet in my mouth, and made me sign a paper.'

Was it a legitimate document?

'I don't know! I just signed. I wasn't accompanied by anyone to say no or ask questions.'

Source: aajtak

And your sisters? 'I've never met them again. My husband's removed their numbers. He claims speaking to them would break our home. I never even handle the phone. And the one time I did, I didn't know who to call. I remember no numbers, no names to cry out to. When I tried contacting my eldest sister, he beat me like cloth. I never dared again.'

Did you ever try to escape or seek police help? Neha flicks her sari as if shaking off dust or bugs, then whispers, 'I wanted to, initially. But then the pregnancy came, one after another, three in total. If alone, I would've fled. But where to with them? I have no one.'

'I did refuse him (the husband), but he wouldn't stop. Escaping the room meant getting beaten. He's quick to anger. Fearing for my children, I stay silent. Not everything is within a woman's control.'

Neha's youthful eyes seem mismatched on her small, weathered face. 'I'll be 20 in a few months,' she says, though it's apparent she's younger. Three children, endless chores, and daily abuse haven't taken the childlike innocence from her eyes—but her voice lacks any vibrancy of a young woman.

Any hobbies or pleasures?

From across the room, the answer comes - 'Of course! Who doesn't have desires? I’ve never stepped out, except to the hospital. I want to see the market, eat 'Fuchka' (her native word), visit my sister's house, wear a saree of my choosing. What life is this? I wear the clothes given to me.'

'Who gave you that saree?' I probe, pointing to the slate-grey fabric in her eyes. 'The neighbor's aunt. It was old. Instead of throwing it, it came to me,' she responds, with straightforward honesty.

'Are you aware that many girls here are trafficked?' I carefully ask. The conversation goes quiet, as the cooler is off. 'I know. It's common here. The one next door came for a lakh. It's the way here. They bring us from our states to marry old men. When they're tired, they sell us to get new ones,' Neha explains. 'How much did they bring you for?'

'Me? I don't know. The intermediary wasn't alone. My sister was there too. Why would she take money!' A self-assuring voice, as if hearing about it for the first time but having pondered over it often.

As we talked, Neha's family entered. While inquiring about welfare schemes, her mother-in-law shares, 'She was an orphan, so we thought she'd manage a household if brought here. She couldn't speak or act according to our customs. She used to search for rice even at night. We barely managed to assimilate her.'

Source: aajtak

Neha, sitting in front, seems to flick away memories from her slate-grey saree, as if clearing away remnants of a previous life.

We then met 42-year-old Meena, who was 'passed through hands' about 30 years ago to Pohri under contract, already having been sold thrice. Images emerged of her being sold and remaining children left behind with their respective fathers. Throughout our conversation, she kept smiling, admitting it felt funny how someone would come from so far just to listen to her story—and she laughs.

Source: aajtak

The scar on her forehead remains, its crease traced by her hand as she narrates the painful account with a laugh.

A husband we met complained about the language barrier with his out-of-state wife. 'The first one cost 10,000 rupees. She couldn't understand anything for a year. I had to direct her for even simple tasks. She couldn't bear a son. Eventually, I had to let her go,' Munna Lal, the husband, shared.

Source: aajtak

Why buy brides? Regional scarcity and past misdeeds were cited; nobody would offer their daughters. This man, still chewing something, displays no nervousness or remorse, dissatisfied with the undelivered promises of the first wife, who did not understand the language or bear a son.

We met many more husbands. A formidable figure, recently abandoned by a much younger wife who took her child to Chhattisgarh, sought help. He makes offers, including covering travel costs, with a strong desire to reunite with his son.

While bride selling is a covert reality in many parts of India, Shivpuri's case stands out distinctly.

Here, a live-in contract, akin to a mistress arrangement, is notarized with a set format dictating the exact conditions, without any more or any less detail. The terms change if the girl is 'fresh' or has been with another before.

We examined two such contracts from this year, portraying the girl's agreement to the terms. They state her possession only of the clothes she wears, avoiding any responsibility for any valuables from a former spouse or parents.

To understand the legal validity of such contracts, we consulted a local lawyer.

Source: aajtak

Anand Dhakad, a senior advocate at the Shivpuri District Court, elucidates - 'The Dhadicha tradition is outright illegal. Girls are trafficked in through brokers, and notaries draft the paperwork. These aren't legal marriages. The poor are exploited by brokers and others.'

He adds, 'Only a mediator knows about the financial transactions, but no amounts are mentioned on paper. There's no set period, like how long a girl will stay with a man. It’s whispered that if a man dislikes the purchased girl, he resells her.'

The stark reality is that these documents, made only for peace of kind, don't hold any standing in court; their validity is at the judge's discretion.

Source: aajtak

A girl may at any time deny consent, stating she was coerced to sign or imprint her thumb, invalidating any supposed consent.

Agents acting as middlemen between needy girls and potential buyers are not hard to find. With established networks across states, they come forward offering solutions.

Source: aajtak

Our encounter with two mediators revealed a promise of wives delivered within days, with prices varying from two and a half to seven lakhs, based on the specifics of our supposed buyer's demand.

The city has numerous brokers with a unique jargon, viewing women as commodities with distinct flaws and features. They're categorized as 'troublesome', 'clean', 'fresh', or 'pre-owned'. Rate negotiations hinge on these criteria. Brokers often target families in grief, with orphaned daughters who can't return home, rendering them more vulnerable to being sold multiple times.

To grasp the legal aspect of human trafficking, we turned to Delhi High Court lawyer, Manish Bhadoria, who explained that if an adult woman doesn't file a complaint, even if she is sold multiple times or abused, there's little anyone can do. For minors, their consent is irrelevant; if a complaint is filed, the law will act.

The severity of charges depends on the trafficker's intent, whether the purchase was for domestic work, sexual exploitation, or organ trade. The penalties range from life imprisonment to the death sentence. But without a victim's report, the hands of justice are tied.