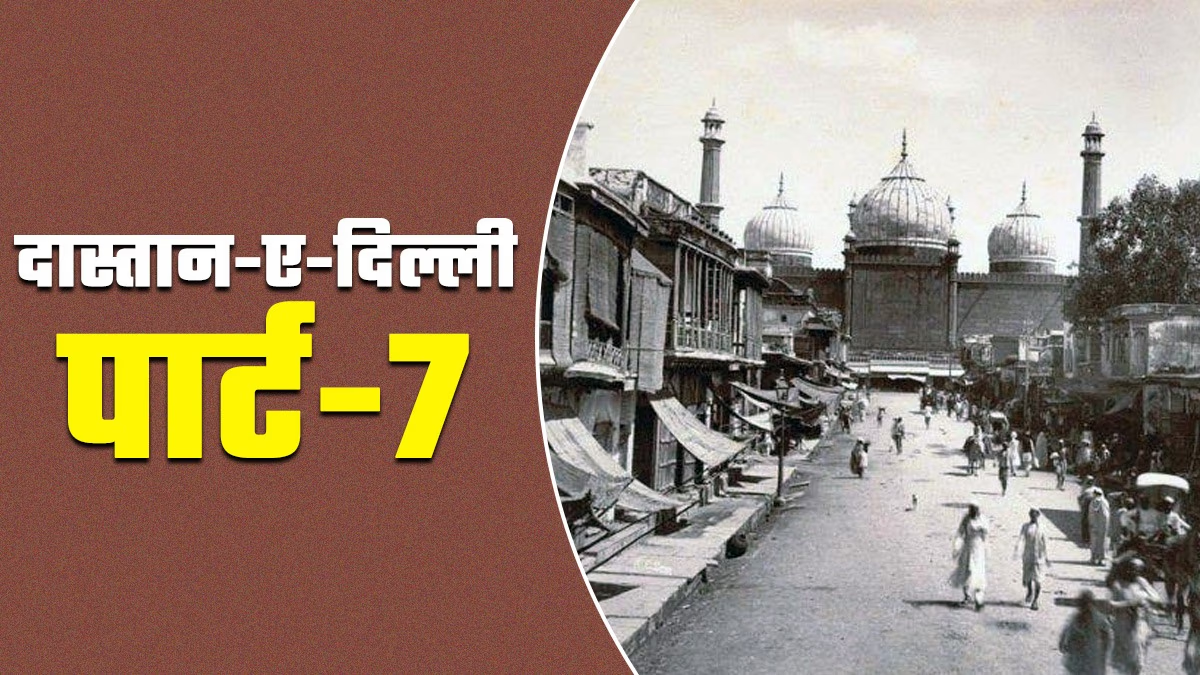

'The era we lived... our children won't experience... now there's only animosity...'

, says 74-year-old Shamsuddin, removing his glasses to reveal nothing but pain in his eyes. When asked who spreads hatred, he candidly responds,

'Humanity has ended, decency has faded, love is gone... people envy others' progress, creating a breeding ground for hatred.'

In 1947, when the country was split in two, Shamsuddin's family endured the pain of partition, moving from Lahore to Lucknow. Dissatisfied with Lucknow, his father moved the family to Delhi the following year, where relatives already resided in Chandni Chowk. The family made it their home. Shamsuddin, born in 1951, has spent his entire life in these bustling lanes, running a small clothing shop that sells everything from bridal lehengas to other clothes for decades.

Shamsuddin, a witness to Delhi's politics from birth, has seen its evolution. When asked about Delhi's transformation, he answers with ease, saying he was born during a time of great activity in the city, shortly after independence. 'I have seen the Delhi of the 60s and 70s as well as today's Delhi. I've seen Indira and Rajiv Gandhi, as well as Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Narendra Modi...'

Source: aajtak

Shamsuddin recalls,

'My father was an ardent fan of Pandit Nehru and Indira Gandhi, and I liked Nehru too. I remember Pandit Nehru visiting Maulana Azad’s tomb near Jama Masjid without security annually. This was talked about at length, as Nehru mingled freely without guards. He was genuinely personable, connecting effortlessly with people. Could you imagine a leader today of such stature moving without security? Even a mere councilor walks with such authority as if ruling a realm.'

Source: aajtak

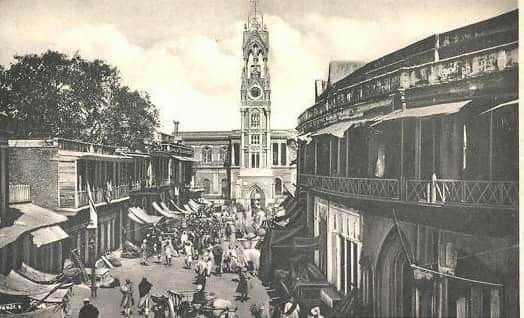

Shamsuddin recollects many Delhi anecdotes. He shares a time when Rajiv Gandhi came to Chandni Chowk for a campaign, opting to forgo security despite concerns over the area being predominantly Muslim and potential risks. He conducted the rally without security -- a testament to Chandni Chowk's hospitality and the distinct era it was, with people of a different temperament.

Ram Gopal, a 45-year Delhiite, echoes nostalgia, reminiscing, 'I often recall those days, when life wasn’t as hectic and loud. There was a steadiness to life. I came to Delhi from Baghpat in the early 1980s, initially living in a small village in outer Delhi, named Hiran Kudna. That village was akin to those in Uttar Pradesh or Haryana. Villages today are a mere shadow of the past unity and warmth.

Neighbours shared meals wholeheartedly, ensuring variety beyond personal fare. You could never pinpoint who your next-door neighbor is now.'

Ram Gopal, retired from a government job, recounts how he moved to Rohini after the 1984 riots following Indira Gandhi's assassination, memories of which linger as vivid. He says, 'I was in Delhi Cantonment on an errand when the news of Indira's shooting spread. Clarity was absent amidst varied rumors until it emerged Sikhs were responsible. Truthfully, the fear felt wasn't limited to Sikhs; Muslims too were gripped by fear.' The chaos and plundering that ensued are indelible after all these years.

Source: aajtak

His wife interrupts, interjecting,

'Sikhs were set ablaze alive... retribution for Indira Gandhi's death. A Sikh family in our lane vanished overnight. We thought it fortunate we weren't Sikhs...'

When asked if such riots could happen again, Ram Gopal opines that the trend of spreading hatred has gone high-tech, with rumors inciting mob actions—the essence of mob lynching today.

81-year-old Kulwant Singh spent a significant part of his life traveling. Known as 'Gypsy Kulwant' by friends, he took off whenever possible. Over decades, he witnessed inhabitation sprawling across many Delhi regions, from open fields in North and West Delhi to majestic colonies replacing forests. The transition of spaces like 'Barat Ghar' in Pitampura to schools and PVRs replacing dilapidated structures in Prashant Vihar remains vivid. His college memories are tightly woven with films watched at the once-thriving 'Alpana' theatre in Model Town.

Source: aajtak

Nostalgically, Kulwant mentions the double-decker DTC buses of the 70s, recalling the five-paisa fares before diesel bans discontinued them.

Shamsuddin, when probed about what he misses in modern Delhi, shares,

'Picnics, a once-thrilling planning event, seem to have faded. The excitement of deciding locations, companions, and items to carry is no longer there. Parks used to host family gatherings, now mostly couples. The tranquility once found is lost, as is the sense of belonging among people.'

Source: aajtak

Corroborating Shamsuddin's view, Akram narrates an incident from 1991 or 1992, when he was heading to Rani Bagh. While crossing a park, he experienced severe chest pain and collapsed. Nearby walkers, including a neighbor, rushed him to the hospital despite the option to simply inform Akram’s wife. The neighbor covered enrollment fees and oversaw his care, an affinity missing today. Recently unwell, a doctor's visits stay unnoticed by a neighbor.