For five years, business was booming. April, May, and June saw such crowds that turning people away was common. Work lasted from morning until late evening. Now, it's different. The events in Pahalgam have scared tourists away. What was once a bustling trade has gone cold, with only hopes pinned on the future.

From horse owners to houseboat operators in Kashmir, the sentiment echoes the taste of diminishing hope. 'What was our fault?' they ask.

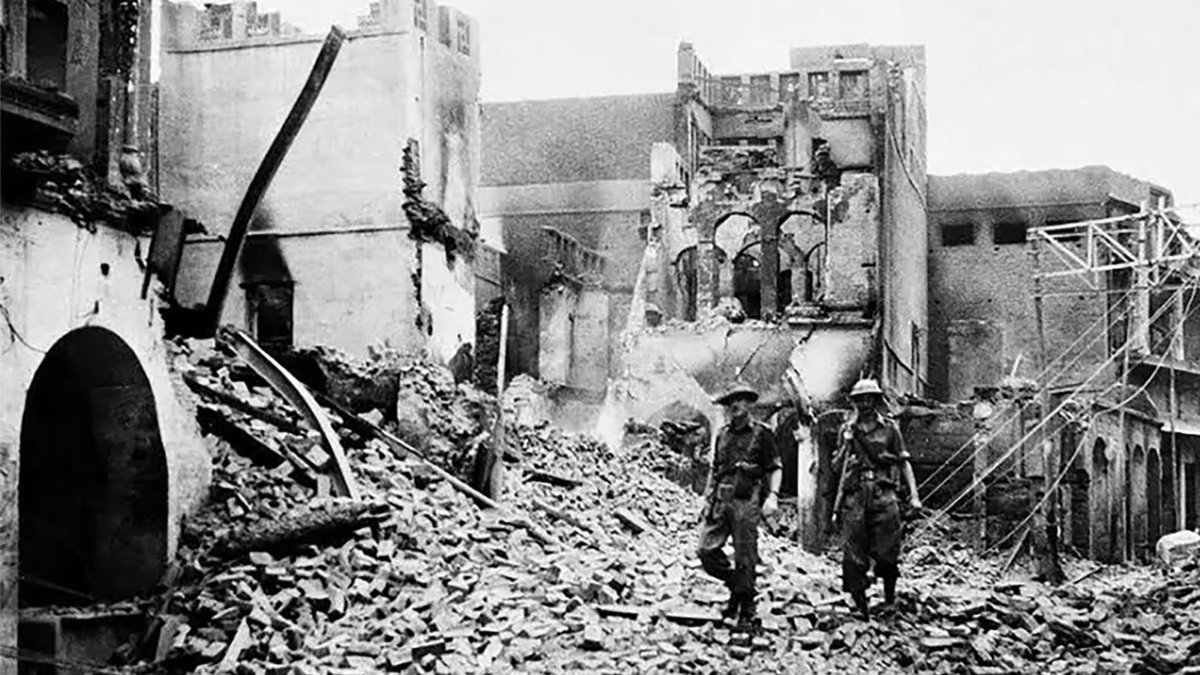

Right after the Pahalgam terror attack, Operation Sindoor was launched. The Indian Army conducted joint operations, dismantling terrorist hubs in Pakistan. Recently, Operation Mahadev targeted the terrorists responsible for the massacre in the Baisaran Valley.

In the meantime, significant changes unfolded. People in Kashmir, a region renowned for its valleys, hills, and lakes, spoke out against Pakistan for the first time. Candlelight marches were held, and tearful street vendors urged tourists to return. The administration promised security. So, what now? Has the valley regained its former vibrancy, or has the silence of 30 years returned?

100 days after the attack, aajtak.in visited to see what has changed and what remains.

In Pahalgam Market and Betaab Valley, many residents depend heavily on tourism. They are still present, waiting in hope, as busyness has turned into waiting.

At the taxi stand, most drivers sit idle. Upon our arrival, a curious crowd formed around us, only to scatter upon spotting the camera.

Source: aajtak

‘Much has been said already, and many rounds of questioning were necessary after so many lives were lost. But now we're starving.’ A taxi driver comments on the condition without giving his name.

Has the situation remained unchanged even now, over 100 days later?

As you can see, there's no outsider here except you. Drivers take turns; one works today, another tomorrow. Where they once earned INR 1500 daily or even more during peak seasons, now it's an occasional 200 or 300.

Surely things have improved somewhat!

Not yet. But there's hope. It is said that the government offers tourists INR 7000 to visit Kashmir. Military and police are stationed everywhere. If all goes well, things might stabilize by the end of August.

The idea of financial incentives for tourism is echoed by everyone, from taxi drivers to shoe shiners. No one knows where this originated, but everyone repeats what they've heard.

Who told you about being paid for visiting?

‘Everyone does. Our association knows it too,’ confides an anonymous taxi driver. ‘If not today, the impact will be seen soon.’

This hope for better days, however, isn't reflected in the data. According to government figures, although more than 23.5 million domestic tourists visited in 2024, alongside over 60,000 international guests, only around 10 million have visited this year, even though the peak season has ended.

In the wake of the attack, about 50 spots were shut down for security reasons. These are being reopened gradually, but many remain closed with no set timeline from the administration.

In bustling areas of Srinagar and Pahalgam, you might see security personnel or none at all.

Source: aajtak

Starting in Pahalgam.

This region has a major stand for pony rides, though previously bustling with demand, now waits with anticipation. Many horse owners refused to speak with us.

Typically a tourist-friendly sector, there's a prevalent anxiety about saying something wrong due to the aftermath of the attack in Pahalgam.

Ghulam Nabi, a young man, finally agrees to talk.

‘We used to earn well. Now, days go by without a single customer. Feeding the horses alone costs INR 300 to 400 daily. They're mute; they can't express their hunger. After all these years, they've sustained our homes. Even without earnings, we can't let them starve. We borrow to feed them.’

How will you repay the debt? Asked a man, his eyes empty as he pondered.

After the incident, some expressed anger at the horse owners for supposedly not helping, though during the attack, they was as frightened as anyone.

Source: aajtak

Sitting on the rock, patting the horse, the young man in the bright jacket is part of the scene from April 22. Bright, yet somber.

Post the pony stand, we explored Pahalgam's market for two hours. Typically crowded streets with shoulder-to-shoulder bustle now lay desolate. Vendors and shopkeepers called out to us. One wholesale trader, Murtaza, approached us.

Enticing us with offers, he's quick to suggest a bargain. ‘Earlier, we didn't need to lure visitors. They’d find us. Now, we too must call out, like hawkers.’

How much do you earn daily? ‘Somewhere around INR 10,000 to 15,000. As wholesalers, we're doing okay. Others aren't so fortunate. Once fully booked hotels are empty.’

Off-record, Murtaza admits many had leased hotels expecting hefty seasonal returns. Now, they pay lakhs in rent monthly with devastating losses. It's dire for many, he whispers, almost like a consolation.

Army and BSF personnel are stationed throughout the market. Talk amongst them reveals a mix of anticipation and wariness.

Source: aajtak

Doesn't this make your job easier?

No. It increases the risk. We stand exposed; yet, if anyone dared, victory would still be ours.

Following August 15, tourism in Srinagar and Pahalgam is expected to recover. In seeking insights on readiness from nearby police stations, we encountered diligent officers already preparing for a shift in activity.

Who’s there at the station?

The clerk is. Feel free to meet them if you like.

Next, we reached Betaab Valley.

Nestled amid pine and willow trees, with the Liddar River flowing, this valley sparkles in hues of turquoise and emerald.

Upon alighting, diverse crowds gather. A little girl insists I take a photo with a dove. Her young brother runs a photography business with rabbits. Shahida, an 11-year-old, is unaware of what transpired in Pahalgam, but knows some died, halting work.

Source: aajtak

Why not free the dove?

Crows will devour them. But for now, they’re alive. She pushes the dove towards me, merely asking for some pittance, before moving on.

In this valley, you’ll also meet Asif Hussain with an album, claiming his photographs rival those in movies.

Near a small stall, Kashmiri attire and jewelry adorn the walls. Asif points them out, explaining that April's incidents brought inactivity. Living off past earnings, his eight-member family continues. Education expenses weigh on him as uncertainty looms.

Do you know what happened in April?

No direct details, we weren’t there.

A fellow photographer, Mohammed Altaf Shaikh, was once Asif's competitor, now a sympathizer. He adds, ‘We held candlelight marches, albeit in vain. Ever since the attack, our people have struggled. Weddings canceled, livelihoods frozen across sectors.'

Emptiness, waiting, and helplessness— these words echo repeatedly in Kashmir.

What were once bustling streets and markets now sit empty, with businesses shuttered and locals longing for a return to normalcy.

Source: aajtak

This trek began in Pahalgam, covering 90 kilometers to Srinagar's Lal Chowk.

Once a vibrant tourist hotspot, now it’s a forlorn selfie corner. After a lengthy wait, no tourists appeared by the clock tower, save me. Nearby, some locals bartered goods— a shift away from the usual bustle.

Weary, I entered a shop, the merchants inside completing a modest meal. ‘In the world of fruit, bananas seem to die the saddest. Fresh today, wilted soon after. This is Kashmir’s fate. Our once-favored land is now shunned. What remains are mere vestiges.’

Dal Lake was our final stop.

Initially reluctant, members of the Kashmir House Boat Owners Association eventually engage. Not fond of media due to past portrayals, Jamir Hussain Butt stepped forward. An award winner in organic farming, his presence is reassuring.

Source: aajtak

‘No one says anything to them, but a mistake here could mean trouble. Anyway, after days of waiting, we’re finally returning our boat to the water,’ states a houseboat owner, introducing Jamir.

Running a shikara, Jamir acknowledges the decline after the attack, ‘From sixty shikaras, only ten are used per day now. Rotating shifts offer meager returns.’

So how do you sustain your home?

‘This hit during our core season. Previously, from April through July, we’d cover the year’s costs.’

Displaying photos of awards and fields, Jamir explains, ‘I fare better. We farm and make mats, so expenses are managed. But seeing friends suffer is bittersweet, praying their liveliness returns.'

He gently leans on the shikara's edge, eyes half-closed in silent hope.