As the serene figure of the Buddha walked through the Jetanavan, a loud, terrifying voice stopped him, urging him not to move. The Buddha heard it and stood still, responding calmly and with great courage, 'I have stopped, but will you?' His calm yet confident demeanour was something Angulimala had never encountered. Emerging from thick bushes, the robber Angulimala, with his grotesque visage, muscular stature, and a necklace of human fingers, faced the Buddha. Robbing and killing travellers was his norm, and today, he had obstructed Buddha's path.

How Did Buddha Transform Angulimala's Life?

Yet, witnessing the Buddha's fearlessness and his brave response, Angulimala was astonished. The Buddha, demonstrating unparalleled composure, accepted Angulimala into the monastic order. Remember, Buddha did not cower or court fear; he faced adversity with courage. This story is not just about the grandeur of non-violence; it also highlights the essence of fearlessness, courage, and strength to respond.

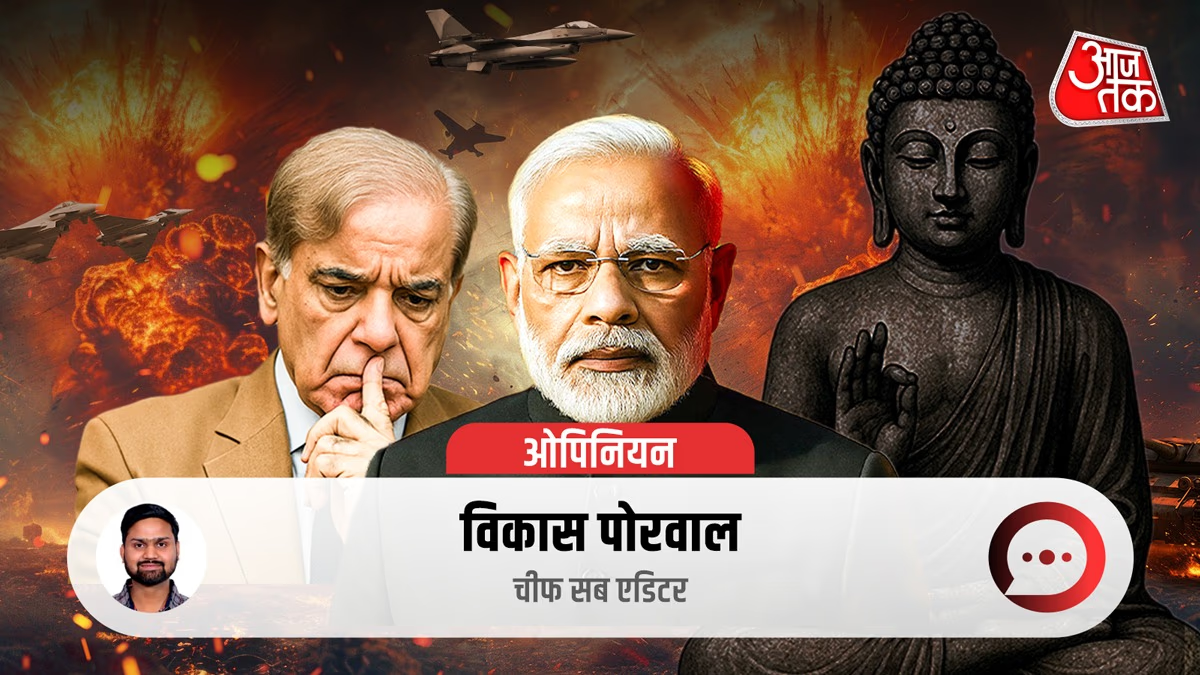

Tales of Buddha and Angulimala are relevant today, especially after the Pahalgam attack when the Indian Army conducted Operation Sindoor. While some try to label India, the land of peace and non-violence, as war-hungry, they misinterpret the teachings of Buddha and Buddhism.

Thoughts on Non-Violence by Buddha and Mauryan History

Indeed, Buddha taught non-violence, deeming violence wrong. Though he hailed non-violence as 'Dhamma', did he advocate standing idly by in the face of injustice? Did he not define punishment? Or address violence imposed by others? Turning history's pages reveals the Mauryan Emperor Brihadrath. Circa 185 BCE, ruling over Magadha was Emperor Brihadrath, who prioritized 'Dhamma' over royal duties following his Buddhist conversion.

Source: aajtak

During his reign, Greek King Demetrius and General Menander had encroached on Indian borders. Historian Hemchandra Raychaudhuri writes in 'History of India' about Mauryan disintegration post-Ashoka, leaving Magadha vulnerable. With anarchy prevalent, the populace suffered.

Many historians note Menander's fascination with Buddhism, which was spreading rapidly in India, yet raised questions about why he brought such large armies. Was he camouflaging a military campaign under Buddhism's guise? Mauryan General Pushyamitra comprehended the threat and prepared the military for conflict in six months, though Emperor Brihadrath rebuked him, questioning the army's assembly.

Pushyamitra responded, 'Majesty, enemies sneak in implausibly. Vigilance against Demetrius and Menander is imperative.'

The Conspiracy of Invasion Under Buddhist Guise?

Enraged, Brihadrath charged at Pushyamitra. However, it's crucial to note that Brihadrath himself was an adherent of Buddhism and peace, yet unable to relinquish anger despite years of devotion. At that moment, Pushyamitra dethroned him, marking the end of the Mauryan Empire. He then founded the Shunga dynasty and successfully repelled Greek invasions.

This historical incident, dating back to 185 BCE, serves as a reflective mirror amidst current situations, showing that non-violence is a personal belief. Still, peace is a collective necessity requiring mutual commitment.

As we revisit the concepts of non-violence and peace, a question arises: Did Buddha teach peace as synonymous with non-violence? Are these seemingly similar concepts fundamentally distinct?

Source: aajtak

Famed American author Paul Fleishman delves into the misunderstandings surrounding 'Buddhist principles', starting with if we misconstrue 'Buddha's non-violence'. His query emerged on September 11, 2001, after the New York Twin Towers attack. In a lengthy essay, Fleishman reflects on non-violence, its impact, and its boundaries stretching to comprehend Buddha's teachings' limitation.

Fleishman's expansive narrative significantly contemplates if there’s indeed a fine line between non-violence and peace or if these similar-looking paths misalign in their essence.

What Do Buddha's Messages of Non-Violence Convey?

The illustrious path of Prince Siddhartha, who became the enlightened Buddha, offers a profound understanding. Siddhartha, born in royalty, achieved enlightenment, placing non-violence paramount in his teachings. Enshrined in the Buddhist precepts, it reads:

"Pāṇātipātā veramaṇī"

This principle, advising against taking life, extends beyond merely avoiding physical aggression to encompass words and thoughts. Buddha intertwined non-violence with compassion and friendship, fostering love for all beings.

However, Buddha never advised royals to renounce responsibilities or amend constitutions based on his teachings. Notably, under Ashoka, who embraced 'Dhamma' post-Kalinga war, widespread Buddhist promotion ensued. Yet, he retained his empire, demonstrating that even as policies softened, penal codes remained vital, symbolized by the royal sceptre.

Violence, Penal Codes, Self-Defense, and Peace

Indeed, Buddha counselled rulers to govern ethically, warning against violence while also reminding the significance of protecting subjects. Buddha recognized that social injustices like poverty could incite violence and wars. While no explicit Buddhist script supports self-defense violence, his teachings do not outright prohibit it.

Source: aajtak

Buddhist Mahayana tradition even deems limited violence in the spirit of compassion legitimate, aligning with Tulsidas’s 'fear leads to attachment' philosophy. Just as Lord Rama sought peace through plea with the sea, taking arms only for coercive measures.

Buddha, as seen, indicated several subtle cues towards the necessity for action against injustice. The Mahavamsa and Pali Canon hold anecdotes like swift handling of crime with compassion by rulers, yet ensuring just punishment.

Doctrine from Mahabharata's Kshama-dharma

Post-Draupadi's disrobing in Mahabharata, Yudhishthira, while advocating patience to Draupadi during their exile, cites the virtue of forgiveness, asserting non-violence until justice becomes indispensable for societal welfare.

Such wisdom is echoed in Ramdhari Singh Dinkar’s poetic lines, illustrating restraint adorning only the powerful, demanding valor amidst peace:

"The bane of enduring tyranny, is losing courage when fearing none. Forgiveness adorns the serpent whose venom spews shivers beneath the sun."

Returning to Buddha, his karma doctrine acknowledges the intent (Cetanā) behind actions, where defensive force, devoid of anger or malice, harmonizes non-violence:

'Not by hatred is hatred appeased. It is by love alone that hate is overcome.' (Dhammapada, verse 5)

Buddha quotes pursue the ideal of aversion-free force in defensive scenarios if compassion-led, like guiding a snake threatening a monk unto a benign path.

The Limits of Non-Violence?

So, what's the threshold? This is situational, revolving around threat assessment. For traditional rulers, Buddha advised minimal corrective and disciplinary measures, emphasizing moral enrichment over punishment.

To Buddha, punishment is violence, yet a last resort:

For Buddha, punishment is seen as a part of violence, to be used cautiously and compassionately. The Bhagavad Gita's teachings align closely - suggesting war as a peace-seeking final resort, but a resort nevertheless.

Source: aajtak

And What Does Krishna Say?

Krishna regards just punishment as essential, endorsing violence not as hostility, but legal and necessary for dharma's safeguarding. The Gita chapter 2, verse 31 encapsulates Krishna advising Arjuna that a righteous ruler must uphold justice devoid of personal animosity.

Law and Order’s Foundation is Danda (Punishment)

The Vedas and Manusmriti signify punishment as the foundation of societal order, a sentiment echoed by Chanakya's Arthashastra: 'Danda enforces dharma, keeping peace and order through lawful power.'

Martial Influences in Buddhist Lands

Observing contemporary countries influenced by Buddhism reveals different portrayals, where Zen, martial arts, and samurais coexist. This coexistence raises compelling questions of harmony between combat arts and dharma, fundamentally exploring self-awareness's aid to spirituality.

Vedic scriptures declare 'Sharira madyam khalu dharma sādhanam' — a healthy body vital for dharma practice. Hence, martial arts nourish physical fitness aiding self-realization, separating the art from mere violence, drawing distinction between punishment and aggression.