Search 'Hathras' on the internet, and before the district details appear, numerous news stories about a Dalit girl's alleged gang rape and murder will flood in. The villains in these stories – four young men from Boolgarhi village. Within days, the village turned into a fortress teeming with armed troops. Several chapters opened and closed since then. It's been four years. The Earth completed four revolutions around the sun, yet Hathras remains shrouded in a dark cloud that no new color can paint over.

As you approach the district's boundary, the scars of the Hathras incident will become apparent. People whisper and shy away when the press vehicle is spotted. Casual remarks near the police station indicate a lingering unease – 'It's September; people will keep coming and going.' Ask for directions to the village, and folks will guide you meticulously from kilometers away.

This tiny village has become a bold, italicized, and underlined piece of news for all the wrong reasons.

aajtak.in tried to unravel these dark pages from 2020 to 2024. In this first part, explore how the accused families have coped over the years. Did they continue to live as families of rapists, or were they honorably cleared by society like the courts?

My son and I were watering the cattle when news broke that a girl was found in Chhotu's field. We went to see. She was calling out for Sandeep…Sandeep.

'Who is Sandeep? Your son?'

No, her brother. Earlier, the girl, her mother, and brother had gone to the field to collect fodder. Then something happened. The landowner asked the girl's brother to come back. He left about half an hour later. By the time we returned, something had happened.

So your son wasn't with the girl!

No, he was with me, watering the cattle. The girl's brother and my son share the same name – Sandeep. This led to the confusion. I told everyone – the police, anyone who came to the village. We cried and pleaded, but no one listened. Everyone focused on the victim. Our truth was ignored, like barren land.

Source: aajtak

The farmer father speaks in a rustic tone. A thin smile crosses his face, amidst his grief. His wife mentions that being a Thakur, he can’t openly cry; people would mock him. He smiles and talks to everyone, but his weak heart requires medication.

People say there was some relation between your son and the deceased.

Not at all. You city folks don't understand village feuds. If someone appears happy, wears nice clothes or eats well, jealousy brews. That's what happened with us. In 2001, the deceased's father accused us of assault.

You probably did get into a fight!

No, they were fighting among themselves. They thought they could extort money due to their caste's influence. Those involved in the fight resolved it among themselves but filed an FIR against us. But we were truthful then and stood our ground. The enmity grew, consuming my son.

Do you meet your son?

Yes, I went last year. His mother often visits. Only the two of us; if one goes, the other stays back. We have cattle to feed and water.

People must mock your family in the village!

Not really. While my son is in jail, no one mocked us. Everyone knows he's innocent. If he were guilty, people would have mocked us.

The only sorrow is that if he were free, he would have been married by now, probably with a child. Who knows what the future holds! If someone convinces the girl's family otherwise, our son might remain unmarried.

The Thakur father wipes his eyes for the first time, his fixed smile unwavering. I turn my gaze to his wife, sitting a hundred meters from the field where it happened.

Source: aajtak

His mother, pulling her small piece of cloth over her head, says, “Don’t ask me about the case or lawyers. We are not educated like you. Just leave us alone.”

The previously passive mother suddenly becomes agitated. Her husband intervenes, “Speak calmly, tell them what we've been through for our son.” He turns to me, “Don’t ask her too many questions. She faints from her illness. It’s harvest time; problems will arise.”

The mother, stepping down from the cot, sits on a dry branch. I sit beside her, turning on the camera, “What’s wrong with you, mother? Are you ill?”

My health has been poor since my son was taken. The doctors say it’s sometimes allergies, sometimes anxiety. They give sedatives, medicines for breathing, for digestion. They’ve told us so many things. If I miss a dose, I lose control.

The Thakur mother breaks down completely, her small veil soaked with tears.

Do you visit Sandeep?

If we gather enough money, I go. He’s in Agra. I can’t go alone; it takes fare for two. When I visit, he cries, “Mom, get me out. Mom, set me free.” How can I get him out? If it were up to me, he wouldn’t be in this state.

You have another son, right?

Yes, he’s in the city, working a 12-hour shift. He’s just 18, much younger than Sandeep. Though he should be studying, he’s already burdened by adulthood. His face reflects the weight of the world when he visits. Both my sons’ lives were ruined by this. As the mother’s sobs intensify, her husband signals her to stop.

Source: aajtak

As I pack up my camera, I ask, “Did you receive any help or assistance?”

No one helps us. If we had help, our young boy wouldn’t be in jail on such charges! You journalists come, wave false flags, then leave.

This time she looks at me intently, trying to match my face with previous visitors. She recalls with scorn, “People came, spat on us, took away everything – documents, mobiles, laptops – everything in the investigation. Who knows when he’ll come back? And if he does, what will he do? We don’t have enough land or any job opportunities!”

Did you ever go to the victim’s house for discussion or settlement?

We didn’t go. Why would we? Their house is visible from our terrace. When we climb up, we see them. We just close our eyes and turn away. Even as she says this, tears stream down her face.

These tears matter little to the crowds gathering in Hathras. Her husband, signaling in the air as if placing a reassuring hand on her shoulder, says, “Drink some water. Calm down, then show them around the house.”

Source: aajtak

About eight families live in a single compound. Each family has a single room and a shared yard. The old-style construction greets you with a strong smell of urine as soon as you enter. I guess the curtained area is the common bathroom.

The first room belongs to Sandeep’s parents.

On request, they fetch a bundle of medications, numerous medical reports. Heart and brain medications. Several prescriptions bear the father's name.

They note, ‘Thakur men don’t cry in public for fear of mockery, so he kept his grief inside. But illness shows no mercy. Four years had turned a young man into an old man.

Several women gather around. Among them, the wives of two exonerated accused. As I try to speak, one woman interjects, “The media is useless. They raised flags of gang rape and murder. Their girl did die, but our husbands didn’t kill her. Even the court knows that. What are you investigating now?” An expression mixing anger and disbelief crosses her face.

With considerable persuasion, one woman agrees to talk but keeps her face covered.

Remove that; we’ll blur your face.

Oh no. Do we trust you? You came earlier, offered sympathy, and wrote lies. Half-covered veil, half-seated on the cot, she scoffs.

Trying to manage the conversation, a younger woman explains, “This is a village. Parents-in-law, elders come and go. If you blur my face, they’ll still recognize me. It doesn’t look good.” She smiles to explain.

Finally, the conversation begins. Ravi’s wife. After three years in jail for the Dalit girl's rape and murder, her husband emerged ‘clean.’ She uses the word herself, a slap on the questioning face.

Source: aajtak

You understand village feuds? It’s rampant here.

Feuds in every household. Over land, over milk yield, even shiny nose rings – any reason can spark feuds. That’s what happened between two families. Different castes, no common ground. Such a massive charge was placed on our husbands without a clue. We had no idea about their plot. People here are sweet but who knows what you’ll write back in Delhi!

Finding myself cornered, I deflect, “So you knew they were innocent?”

Of course. He’s my husband, always calm, never raised his voice or looked at anyone unfairly. Now, why would he, along with his nephew, do such a thing? Everyone knew they were framed. We visited him every few days in jail to keep his spirits up. Brought the kids too.

How did you manage expenses for three years while he was in jail?

We worked. Laboring in fields, just like the standing paddy and millet crops now. We harvested, fed others’ cattle. Worked while soothing sobbing children. One child was so young that I worked while holding him. Now they’re school age, but where’s the money to educate them?

He’s back, but no job. The village knows he’s innocent. Hathras market does too. But knowing is a problem. People who greeted us now avoid us, fearing their enmity might entangle them.

Everyone reassures us, but no one offers work.

Where is your husband now? Can we talk to him?

He went to his sister’s place. No job here, just nosy people asking questions. He got frustrated and left. We’re here waiting for the harvest season to work.

Hiding her sadness behind anger, she bites her veil. I point to the saree, “You must buy new clothes during festivals.”

The response comes from the surrounding group with shared laughter. “We barely manage food, forget new sarees. See these ornaments? All fake. Not a single genuine piece.”

Ravi’s wife remains seated, biting her veil.

Source: aajtak

The third accused, Ramu’s family, also resides here. His wife refuses to talk. “Why?” “You media twist truths; if something happens, my husband will be blamed again!”

The group repeats in unison.

A young girl pursuing her BA remembers, “Many came four years ago, making videos, promising to show our side. Nothing happened. We bore the blame. Now my uncle is free, but life isn’t the same. No work, no status. Paranoia persists, fearing more trouble. That’s why the women are scared. As women, our outbursts can escalate issues.”

With weighty eyes reflecting exhaustion, I abandon attempts to talk further and exit, through the smell of urine and waiting.

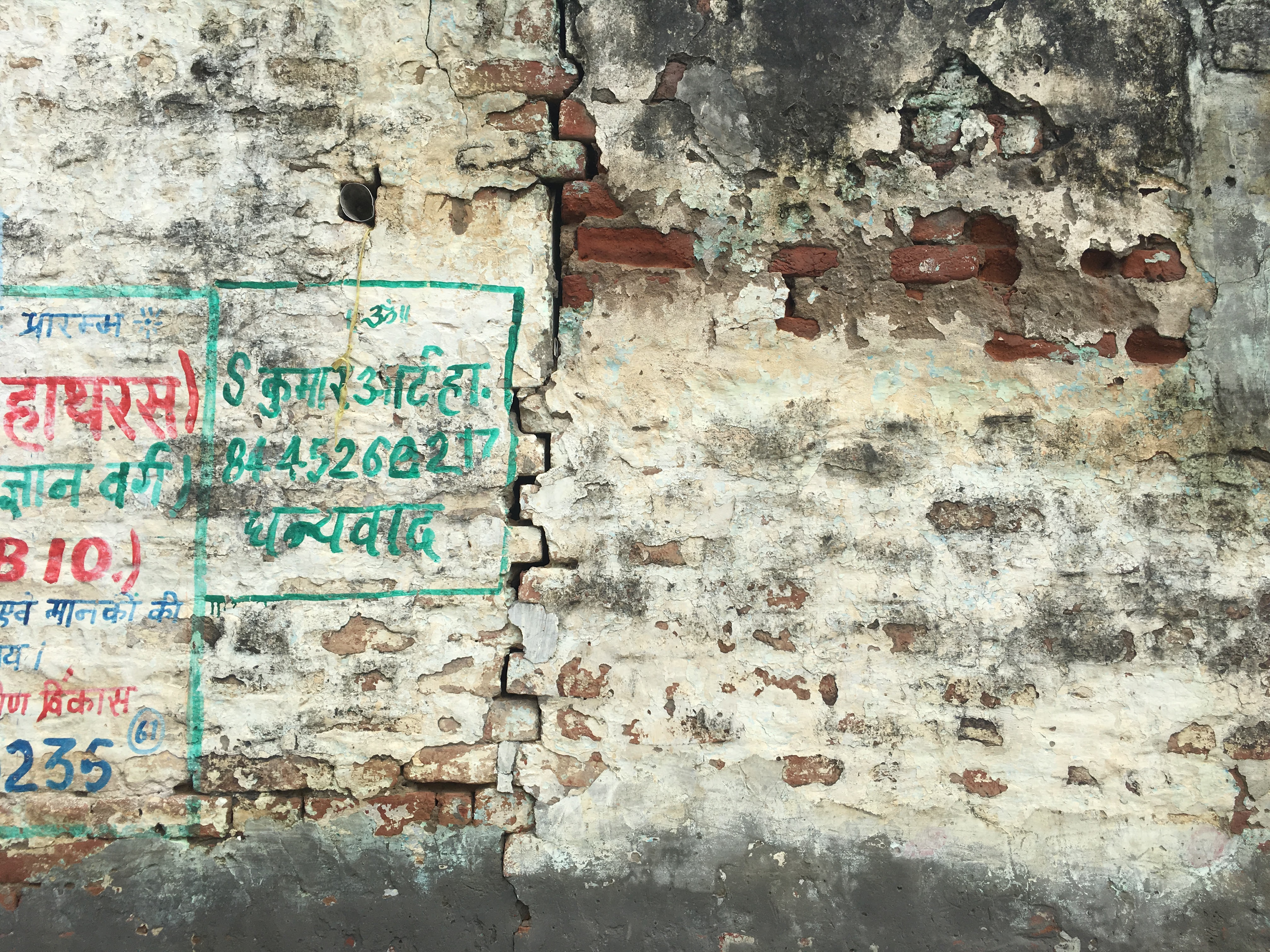

On the communal home’s outer wall is an art studio’s green advertisement with a contact number. From the crumbling wall to the broken spirits inside, perhaps this alone shows any vitality.

Source: aajtak

A few meters away is Lavkush’s home. Another young man exonerated last year along with Ravi and Ramu. Innocent but only in title, as his house now bears a lock. A villager remarks, “They left. Staying here held no prospects – no new jobs, no old respect.”

(In the next part, learn about the story of the Hathras victim's family. For four years, they've been living under a kind of house arrest in the name of safety, almost isolated on Earth. No one visits their home; even for buying vegetables, they need permissions, escorted by four to five security personnel. The daughter’s ashes await justice, while the family awaits the fulfillment of government promises.)