After leading the interim government for eighteen months, Mohammad Yunus stepped down, leaving behind a strategic political tapestry that poses risks for every move new Prime Minister Tariq Rahman makes. Outwardly, it might seem like a victory crown, yet beneath lies a tangled web. This is more than a mere power shift; it's a complex web woven with the last decisions Yunus made.

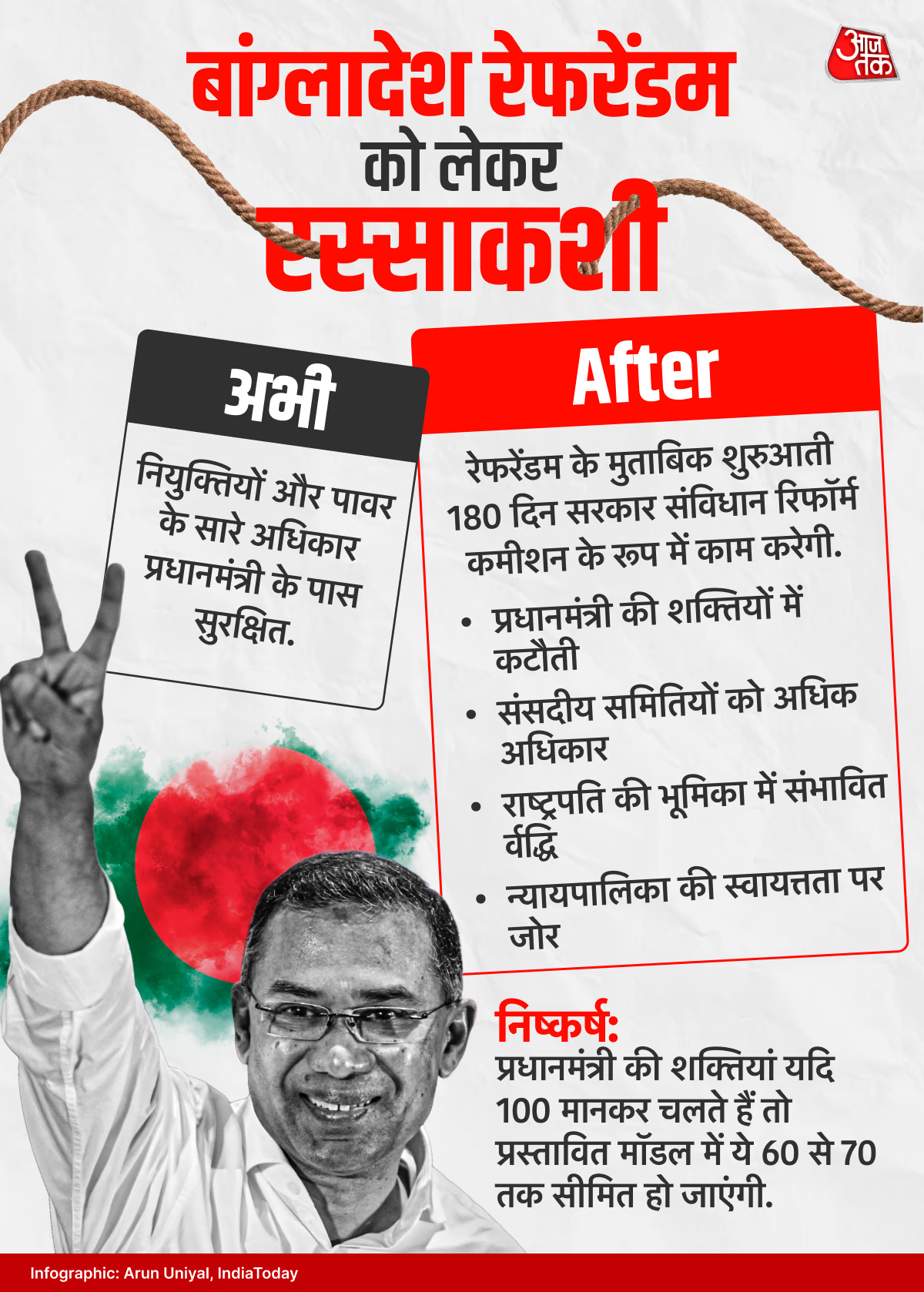

There were widespread reports suggesting Yunus was hesitant to hold elections, yet domestic and international pressure forced his hand. Moreover, he introduced a referendum without constitutional precedence in Bangladesh, under the guise of constitutional reform and parliamentary system rectification, where voters participated during the elections. This referendum functioned like a blank check, allowing only 'yes' or 'no' responses from the people.

Now that the results favor 'yes', the onus is on the government to shape the new administrative landscape of Bangladesh. This is where Yunus' ulterior motive possibly starts to surface, posing a dilemma for Tariq Rahman regarding whether to initiate constitutional reforms or not.

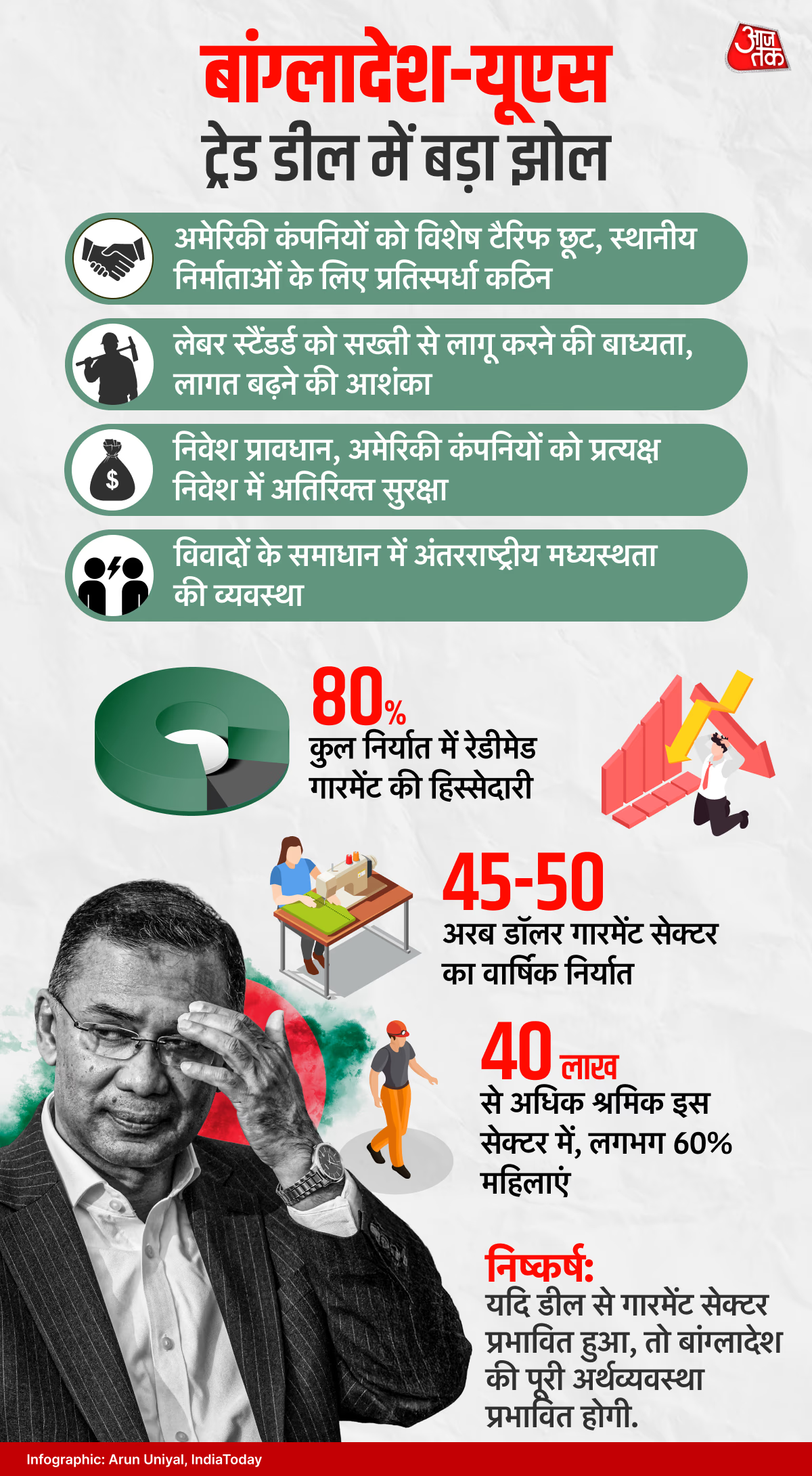

Just before the elections, the Bangladesh-US trade deal threatens to become a thorn in Rahman's side. It contains provisions related to Bangladesh's crucial textile sector that could adversely impact local businesses, raising questions about Yunus’s move as an interim leader to make decisions reserved for the new government.

Constitutional Reform: Looming Shadow over Power

Rahman's biggest predicament involves constitutional reforms. Before the elections, the Yunus government held a referendum, arguing a need for a new parliamentary system—restricted powers for the Prime Minister and stronger institutions. While appearing as democratic reforms on paper, political fate doesn’t rest on paper. Under the referendum, the new government must work as a constitutional reform commission for the first 180 days, substituting the traditional cabinet form.

BNP isn't at ease. Their MPs have yet to take oath as commission members. Clearly, they joined through elections, not to be part of a commission. BNP fears this system could obscure the elected government's supremacy, a structure possibly stemming from and influenced by Yunus’s ideology. In politics, intention is as significant as suspicion, and suspicion runs deep here.

Source: aajtak

Jamaat and Student Politics’ Strategic Moves

The opposition coalition, especially Jamaat-e-Islami and the student organization National Citizens Party, won’t let go of the reform agenda. They will assert it as part of the electoral mandate, emphasizing voter-decreed reforms. They argue Prime Ministerial power must be checked lest the new Prime Minister turns autocratic like Sheikh Hasina.

In Bangladesh, the executive branch has prevailed for long. The Prime Minister enjoyed ample power over appointments, security control, and administrative authority. Reforms signify the decentralization of these powers, potentially strengthening parliamentary committees, enhancing the President's role, and possibly granting more judicial autonomy. Nonetheless, the balance of power undergoes political negotiation. Jamaat and student groups will leverage this situation to exercise pressure politics.

Should BNP hesitate on reforms, it might be portrayed as opposing the electoral mandate. Hastening reforms could dilute its own strength. This is perceived as Yunus’s strategic move—the new government is left to either reduce its influence or endure ethical pressure.

The Real Knot in the US Trade Deal

The other significant puzzle is the trade agreement with the US. Critics claim speeding the Bangladesh-US deal just before elections was a political maneuver. With voting scheduled for February 12, the deal was made public on February 9. If transparent, why was it disclosed late, they question?

Bangladesh’s economic lifeblood is the textile and ready-made garments sector, contributing almost 80% of exports, employing millions, notably women workers. The US serves as Bangladesh’s prime export destination, receiving the bulk of its garments.

Emerging information indicates concessions granted to the US detrimentally compromise Bangladeshi interests, such as tariff modifications, relaxed investment rules, and stringent labor conditions. The utmost contention surrounds the US-imposed ‘Cotton Clause’ promising zero tariffs only for garments made from raw materials or yarn purchased from the US. Concerns grow that special access to American companies in Bangladesh might pressure local industries.

Consider imported raw material constraints or direct control over production by American brands; Bangladeshi manufacturers might struggle with profitability. Global market competition is already fierce, with Vietnam, Cambodia, and India making strides in affordable production, while regulations tighten in Europe, possibly hindering Bangladesh’s export momentum if this US agreement proves adverse to local industries.

Textile sector growth transcends statistics for Bangladesh; it's a social stability pillar, critical for countless families’ income, foreign exchange reserves' sustenance, and Bangladesh’s urbanization hub.

Source: aajtak

Rahman at the Crossroads of the Deal

Tariq Rahman stands before three paths...

First-

Accept the deal as is, publicly declaring the interim government's decision as nationally beneficial. This might maintain smooth relations with the US but could dissatisfy local industries, including BNP’s business base.

Second-

Announce a deal review, forming a committee for reevaluation. It would be a strong domestic gesture, yet viewed with uncertainty by the US, potentially unsettling investors.

Third-

Attempt partial amendments—seeking consensus not conflict. This path seems pragmatic yet demands exquisite diplomatic balance.

Rahman's Political Dual Front

Retreating from constitutional reform risks being branded power-hungry by the opposition. Progressing reform might limit his power. Challenging the US trade deal risks US estrangement, whereas acceptance could alienate industrialists and workers.

Yunus might have exited, but his structures remain influential in Dhaka. For Tariq Rahman, the crucial concern isn’t self-satisfaction in his role as Prime Minister but maintaining its authority. Successfully balancing these challenges would demonstrate his political acumen; falling short might imperil his government early on. Yet again, Bangladesh’s politics arrives at a critical juncture, where the stakes involve not merely governance but broader systemic and economic dynamics.